January 3, 1945 — The return of a leader and welcome additions for the 30th Regiment

January 3, 2025

January 4, 1945 — Phil’s celebrates his 20th birthday on the front In Europe

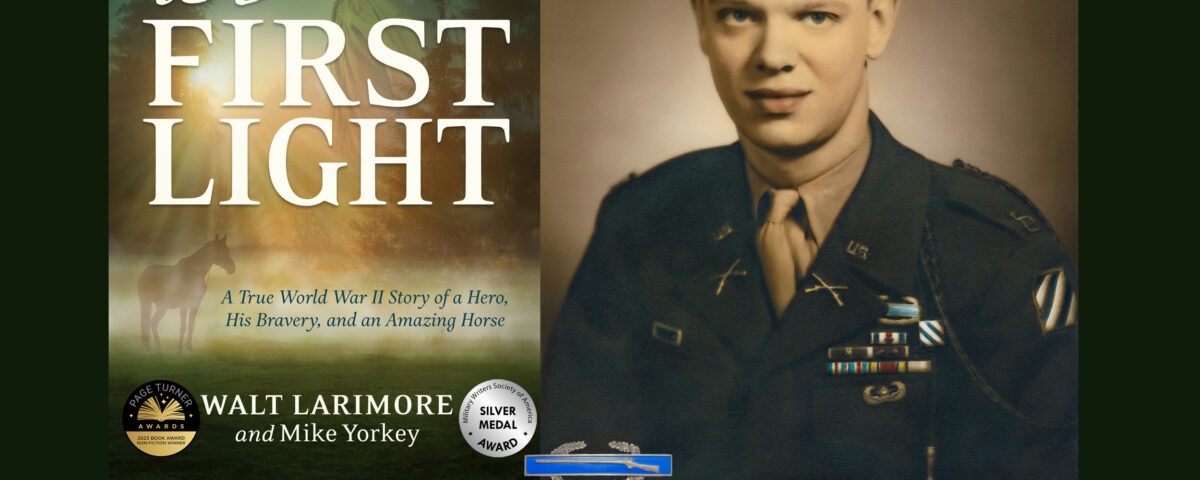

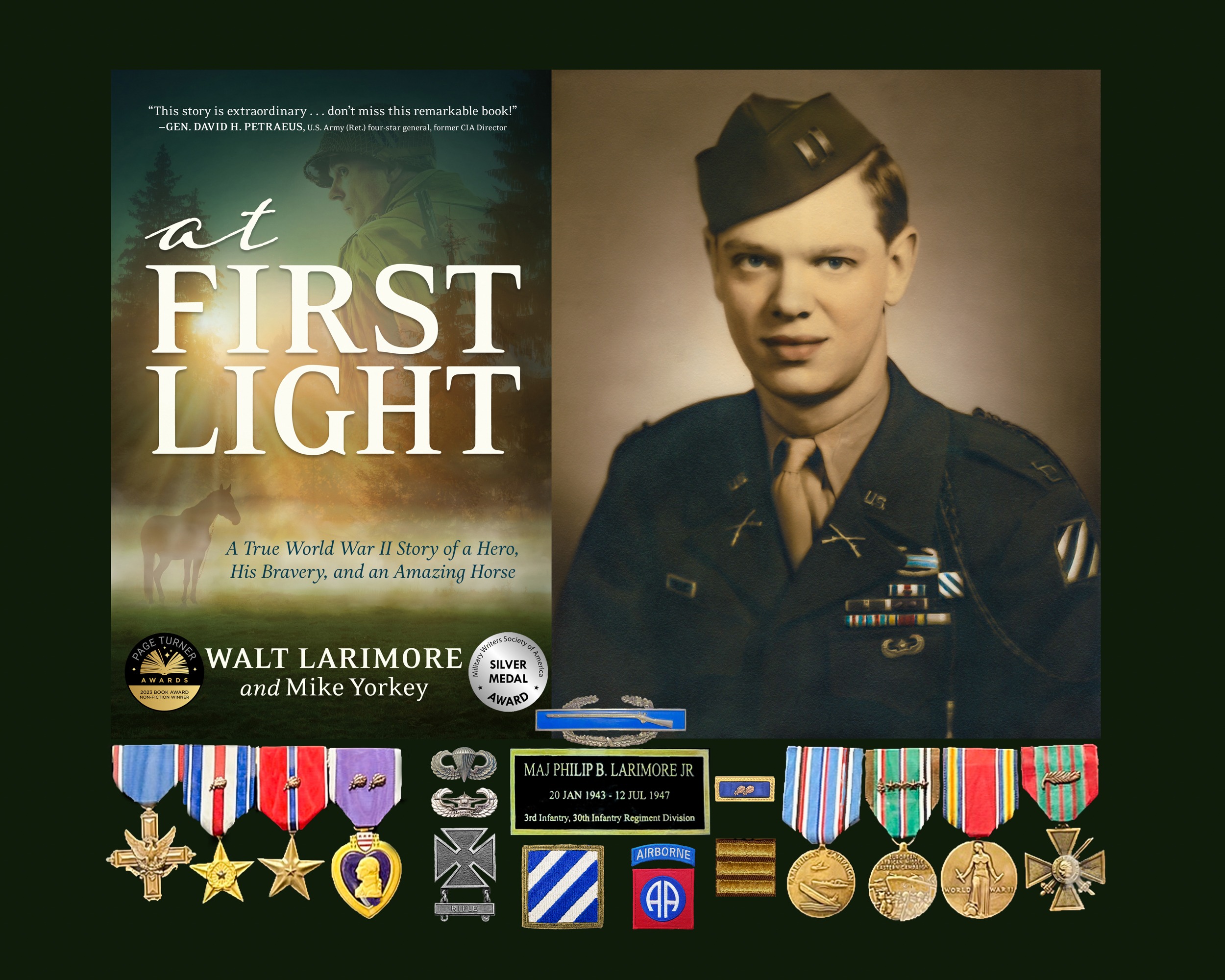

January 4, 2025Today would have been my father’s 100th birthday. He was an amazing man—a teenage war hero, a beloved professor, a revered Boy Scout leader, and a loving husband, father, and grandfather. This brief biography is in remembrance of him. After spending over 15 years researching his past exploits and adventures for my book about him, At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse, I ended that book with these words: “Dad, I always loved being your son. Now more than ever, I’m honored by it.” Happy heavenly birthday!

The world was a simpler place when Philip B. Larimore, Jr., was born on January 4, 1925, in Memphis, Tennessee, the only child of Philip Sr. and Ethyl Larimore. He was a latchkey kid because his father was a Pullman conductor for the Illinois Central Railroad and his mother (center below—holding Philip aloft) was a legal secretary.

Growing up, Phil was undisciplined and a whirling dervish of energy and mischief. Most schoolwork didn’t interest him; he preferred to swim, hunt, fish, and ride horses. When he was six years old (below left) his mother took him and some friends for his birthday to see the world-famous Lipizzaners. He vowed he’d get to Europe to see them one day (and he did). On his 9th birthday (center below), on a dare, he and his best friend swam both ways across the Mississippi River at flood stage. His school years became so challenging—to Philip and his teachers—that at 13 years of age his parents sent him to Gulf Coast Military Academy (GCMA) in Gulfport, Mississippi, where he boarded during his high school years (his freshman year photo below right).

At Gulf Coast Military Academy, Philip excelled at military history, strategy, tactics, and weapons, and became adept at competitive shooting, compass work, and close combat. He was a born-leader and his gifts and talents blossomed in his years at GCMA. During his senior year of high school, he met Marilyn Fountain (second from the left with her suite-mates, bottom center photo), a freshman attending nearby Gulf Park College, and would remain close to her during his time in the military. His parents attended his graduation in the spring of 1942 after America went to war following Pearl Harbor (left below, graduation photo right below).

After becoming the youngest-ever (and only ever 17-year-old) graduate of the Army’s Officer Candidate School (OCS) at Fort Benning, three weeks shy of his eighteenth birthday, Phil underwent another year of training before being transported to Naples, Italy, in January 1944 where a military band playing in the streets welcomed him (left below). He first saw action in the Battle of Anzio, as a platoon leader for a front-line A&P (ammunition and pioneer) platoon, becoming of the front-line commissioned officers in the war. At Anzio (center below) the Germans, who occupied the surrounding mountains, pinned down the GIs in muddy, flat, mosquito-infested farmland for over three months. After a vicious breakout from what they called the “Bitchhead,” the Allies liberated the first European capital, Rome, on June 4, 1944 (below right) just two days before D-Day on Normandy.

As a 2nd lieutenant in charge of a frontline platoon at Anzio, Phil was one of the, if not the, youngest frontline commissioned officers in the European Theater of Operation at the age of nineteen and won his first medal—the Silver Star (the Army’s third-highest decoration, below left). After liberating Rome, the men trained for and participated in their fifth Divisional Amphibious D-Day of the war—which followed their D-Days at French Morocco, Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio. He wrote home, “Enclose[d] you will find the little U.S. flag (below center) I wore the day we made the invasion of Southern France.” He added, “Sorry I won’t be home for Christmas but going to try like hell to be in Berlin I betcha.”

Somewhere in France, Phil is standing behind the door of his military jeep (below left), which he named “Monk,” a nod to his girlfriend Marilyn Fountain, whom he nicknamed “Monk” after her hometown of Des Moines, Iowa (“moines” being the French word for “monk”). Fellow officer Lt. Abraham Fitterman is sitting atop a massive German railroad gun (below right) used at Anzio that was called “Anzio Annie” by the GIs. The seventy-foot barrel had an eleven-inch diameter and could propel 500-pound projectiles up to forty miles and create a crater large enough to swallow a Sherman tank. While fighting in France, Phil was awarded his first Purple Heart, and two Bronze Stars (the Army’s fourth-highest valor decoration).

Phil’s mother received the Western Union telegram (the lowest one below) about Phil being “slightly wounded” in the Vosges Mountains in France on “27 OCTOBER” 1944. It was serious enough that Phil recuperated in a field hospital for almost two months. Part of that time was in a bed next to World War II hero Audie Murphy. Another telegram (just below) was received after her son was “seriously wounded” in Germany on “08 APR 45.” Both resulted in battlefield decorations including his second and third Purple Hearts (both were Oak Leaf Clusters), a second Silver Star (the Silver Star with an Oak Leaf Cluster), and a Distinguished Service Cross (the Army’s second-highest valor decoration after the Medal of Honor).

Following the amputation of Phil’s right leg below the knee in Germany only one month before the end of the war, he spent a year at Lawson General Hospital (left below), an army hospital specializing in the care of amputees in Atlanta, receiving additional surgeries and undergoing intensive rehabilitation. Phil is pictured to the in a newspaper clipping (center below) after reuniting with his army buddy, Capt. Ross Calvert in Nashville, Tennessee. They are helping Sgt. A. P. Mays into a civilian sport coat. At this point, Phil was still on crutches, unable to wear a prosthetic leg. In his Captain’s portrait (right below), Phil is wearing several of his battle awards. The striped patch on his left shoulder represents the “Blue and White Devils” of the 3rd Infantry Division. Phil was wounded six times in battle but refused three of the six offered Purple Hearts.

Marilyn Fountain and Phil had an off-again, on-again relationship after they met in Gulfport, Mississippi, when Phil was a senior at Gulf Coast Military Academy. Both in school and after being reunited following the war, they shared a love for horses and equestrian activities.

While preparing to appeal the Army policy of automatically discharging Army officers who were amputees after they completed rehabilitation, Phil’s former commanders, along with his best friend, Ross Calvert, worked to get him assigned to the Military District of Washington. One of his tasks was attending the visits of dignitaries. Phil is standing next to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, (seen just at the right of Eisenhower’s shoulder) and British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. In the center picture below, Phil is seated to the far left, next to Marilyn Fountain. In the foreground on the far right is Colonel Lionel C. McGarr, Phil’s 30th Infantry Regiment commander. In the bottom right photo, Phil is assisting his 3rd Infantry Division commander, Brigadier General John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel.

Phil’s closest friend in the military was Ross Calvert (left photo, standing to the right with Phil seated). They were together at Officer Candidate School training at Fort Benning and would fight together in epic battles against the Germans. Phil was held in high esteem by his superior officers, including Brigadier General Robert. N. Young, Commander of the Military District of Washington after the war (center below), who wrote on his autographed portrait, “With great admiration of Phil as one of the outstanding combat soldiers in World War II.” In the bottom right photo, Phil receives the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest decoration from Colonel John J. Albright, the Commanding Officer at Fort Myer next to Arlington National Cemetery.

After Phil received the Distinguished Service Cross in a ceremony at Fort Myer, his story was featured in this newspaper clipping that noted how he was the youngest man commissioned as an infantry officer during World War II. Shortly after this photo of him and “fiancée” Marilyn Fountain was taken, the couple called off their wedding plans. Around the same time, Phil was written up in newspapers around the country after successfully bidding $50 for his beloved war steed, Chugwater. during an army auction of surplus horses.

He was honorably and medically discharged from his beloved Army on July 12, 1947, as a Major. and was authorized to wear

- Distinguished Service Cross

- Silver Star with Oak Leaf Cluster

- Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster

- Purple Heart with Two Oak Leaf Clusters

- European Theater of Operations Campaign Medal with Four Bronze Stars & Arrowheadi

- Presidential Unit Citation with Two Oak Leaf Clusters

- Fourragère and Croix de Guerre with Palm—France

- American Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- Combat Infantryman Badge

Auctioneer Byron Brumback made a special request to the audience: “I want to ask a favor right at the start. I want to ask you not to bid on horse number five,” referring to Chugwater.

Phil and Chugwater were a match made in heaven, but because Phil had lost his right leg, he had to teach his horse how to respond to his “one-leg lead,” meaning his left foot and knee movements. Chugwater, a ten-year-old bay gelding, was quite a jumper. After the war, Phil loved participating with “Chug” in formal foxhunts, where he served as Field Master, being part of horse shows, and engaging in steeplechase competitions.

In the spring of 1949, Phil met a young nursing student, Maxine Wilson, in Memphis, Tennessee. They quickly fell in love and were married on June 21, 1949, after her graduation. Phil continued his studies, earning both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in geography from the University of Virginia. Two of their four sons were born in Charlottesville, Virginia. After graduation, the family relocated to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

This is Phil’s official photo (bottom left) while pursuing doctoral studies and later directing the Department of Cartography (map-making) at Louisiana State University. Phil, a former Eagle Scout, loved involving his four sons in the Boy Scouts—all of whom became Eagle Scouts. Maxine places the Silver Beaver Award, the distinguished service award of the Boy Scouts of America, around Phil’s neck. In the bottom middle photo. At Phil and Maxine’s 50th wedding anniversary celebration in 1999, (below right) Phil began sharing stories about his exploits during World War II—the first time he had done so with his children. Following Phil’s death several years later, his son Walt Larimore began going through scrapbooks and spent over fifteen years investigating Phil’s movements during the war, which led to the writing of At First Light.

“Mac” is pictured with her boys (from the left): Walt, Billy, Rick, and Phil at Phil’s funeral in Baton Rouge in 2003.

This is from the Epilogue of my book about dad, At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse.[1]

During the last few years of his life, Dad more frequently shared his stories with family and friends. He answered the questions my brothers and I asked. One of the positive consequences of sharing his stories was that his pain

waned, and his sleep became calmer and more tranquil. Dad finally seemed to be at peace with his past, hopeful for the future, and secure in knowing that he had served his country honorably.

Philip Bonham Larimore Jr. died a happy man, in his sleep, on October 31, 2003,[2] and was buried at Port Hudson National Cemetery just north of Baton Rouge. An Army general from the Pentagon called our home just after Dad died and told me that there was a special plot reserved for him at Arlington, not far from where his friend, Ross Calvert, was buried. The Army would transport his body for burial with full military honors, if that was our wish, and the family could accompany him.

When I told Mom, she just shook her head. “That’s very nice, but he wants to lay in rest close to home. And I’d like to have him nearby also.”

Despite his distinguished service, the only honor guard the Army could muster for his burial was two elderly volunteers wearing Veterans of Foreign War (VFW) caps who played a cassette tape of “Taps” from a cheap portable boombox. It wasn’t that the Army didn’t care or didn’t want to honor his fantastic feats on the battlefield, but with over four million living World War II veterans at the time, this country was losing more than a thousand soldiers every day. Along with the war losses in Afghanistan and Iraq, there was no way to keep up.

Before my mother’s death three years later in 2006 at the age of eighty,[3] she gave me his old military footlocker, which contained hundreds of his personal letters and the published histories of the 30th Infantry Regiment and 3rd Infantry Division. I also found a half dozen scrapbooks jammed with magazine and newspaper articles saved by my grandmother. These accounts confirmed his amazing stories and the exploits of the brave soldiers he fought with on the “forgotten fronts” of Anzio, the Vosges mountains of France, the Colmar Plain, and thick German forests and well-protected villages.

Dad told me one time, “The Northern Front guys had one D-Day; we had seven. The Northern guys had one Battle of the Bulge and one Battle of the Hürtgen Forest—and so did we. But who knows all that?” My father was referring to the five 3rd Infantry Division amphibious assaults in French Morocco, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and southern France as well as two of his 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment’s amphibious attacks on Sicily. He was also referring to the bulge at the Battle of the Colmar Pocket and the dreadful battles in the forests of the Vosges Mountains.

Dad’s stories proved to be enthralling and horrifying—and undoubtedly worthy of recounting. Furthermore, his adventures as a master equestrian before, during, and after the war added to his captivating chronicles. And finally, I felt his struggles of being an amputee fighting to remain on active duty in the Army he dearly loved deserved to be told for future generations.

I began transcribing Dad’s letters and recording the stories he told my brothers, his friends, and me. Where the accounts differed in minor ways, I always chose the storyline most consistent with others. I researched historical accounts of his battles and World War II in hundreds of books, memoirs (some unpublished), periodicals, newspaper articles, and websites. I interviewed a few of the remaining men he fought with and the children of others. I traveled to and spent months studying exhibits and documents at archives, museums, posts, forts, redoubts, and stables.xi The information I discovered allowed me to fill in holes and add color and detail to an already incredible story.

I began formulating more than a decade’s worth of work into what I thought might be an interesting novel, but trusted writing colleagues strongly urged me not to fictionalize the story. Jerry B. Jenkins, a New York Times best- selling author and a dear friend, told me, “A novel needs to be believable, and a nonfiction book needs to be unbelievable. Your dad’s story is the latter. Make it nonfiction.”

So it is.

At First Light is the result of more than fifteen years of dogged research and endless writing and rewriting, and I’m proud to honor my father’s legacy as well as the men he fought with and the women who aided in his recovery.

Plus, it’s unbelievable—and all the better for that!

Someone gave Dad a copy of Stephen E. Ambrose’s Citizen Soldiers with the following note inside: “This is a wonderful book that tells a great story about men like you…. It is about you…. I did not fully realize who you were until I saw you through these great stories. Our nation owes you and many others a great debt. I always enjoyed our friendship; now I am honored by it.”

I would echo his sentiment.

Dad, I always loved being your son. Now more than ever, I’m honored by it.

~~~~~

As a result of the book:

- On August 1, 2023, the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division inducted Dad (posthumously) into their Marne Hall of Fame at Fort Stewart, Georgia. Dad was inducted along with General Marshall, General Eisenhower, General Ridgeway, and his two commanders, General O’Daniel, and General McGarr. Dad is one of only 30 men who have been inducted into this Hall of Fame. What a wonderful honor. My brothers and I were able to attend together along with our spouses and kids.

- Also, the LSU Military Museum in the LSU Memorial Tower in Baton Rouge opened a special exhibit honoring Dad in October, 2023. It will be there for at least a year and the museum entrance is free.

- Finally, General David Petraeus nominated Dad to be considered for the Army’s Officer Candidate School (OCS) Hall of Fame at Fort Moore (formerly Fort Benning), Georgia. In December 2024, I was notified that he was chosen. The induction ceremony will either be in March 2025. That year will be the 100th anniversary of his birth and the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe (VE-Day).

Though by no means a best seller, this book had better reviews and won more awards than any book I’ve written. The awards so far include:

- 2023 Non-fiction “Book of the Year,” The Golden Author Award, and the “Book of the Year” in the Genre “True Stories, by the International Page Turner Awards (London);

- 2022 Silver Medalist for “Book of the Year” by the Military Writers Society of America;”

- 2023, One of only 10 books chosen to be a Featured Book at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans; and

- 2023, a “Featured Book” at the Louisiana Book Festival in Baton Rouge.

The reviews so far have been excellent. Here are snippets from just a few of the many wonderful reviews:

-

- A masterful retelling of a heroic life … finely written and well-researched … a beautifully told story.”

- “Like a movie plot … stranger-than-fiction.”

- “Like a melody building to a crescendo … gains power as it proceeds to a moving conclusion.”

- “A riveting story that rivals Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken.”

- “An impressive and memorable story of genuine courage, daring, and heroism.”

- “Never before has a book moved me to tears out of pride.”

- “This story is extraordinary. Don’t miss this remarkable book.”

- Gen. David H. Petraeus, U.S. Army (Ret.) four-star general and former CIA Director

- “Quite moving … I can’t describe the conclusion to friends without tearing up.”

- Karen Jensen, Editor, World War II Magazine

- “At a time when we need real heroes more than ever, this story should inspire, bless, and encourage every American.”

- Cal Thomas, nationally syndicated columnist

- “This true tale scores in spades … may keep you up till first light.”

- Jerry B. Jenkins, New York Times best-selling novelist

- “It’s like a combination of Band of Brothers and War Horse—or perhaps a mixture of Unbroken and Seabiscuit. A mesmerizing page-turner not to be missed.”

- Pat Williams, co-founder of the NBA’s Orlando Magic and former general manager of the 1983 World Champion Philadelphia 76ers

- “An astonishing … compelling … superb story of courage, honor, and sacrifice.”

- Lt. Gen. Robert L. Caslen, U.S. Army (Ret.) three-star general, formerly the 29th President of the University of South Carolina and the 59th Superintendent of West Point

- “A fantastic story … deserves a standing ovation.”

- Mike Krzyzewski, former Men’s Basketball Coach at Duke University

I’m delighted that as of 06/01/24, the book had received 575 ratings with about 96% (529) being 5-star ratings:

- Amazon (248 ratings [228 5-star]),

- GoodReads (148 ratings [123 5-star]),

- Barnes & Noble (80 ratings [79 5-star]),

- Walmart (55 ratings [53 are 5-star]), and

- Target (44 ratings [all 5-star]).

~~~~~

[1] Larimore, Walt and Mike Yorkey. At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse. Knox Press. Nashville, TN. 2024 (updated edition).

[2] My father was admitted to the hospital on the evening of October 30, 2003 with abdominal pain. A

nurse found him dead at about 3 a.m. She said he looked peaceful. We didn’t ask for an autopsy, but with

a history of smoking heavily most of his life, which led to atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) and

coronary heart disease (he had had a heart attack a year earlier), my guess is that the pain was from a leaking

or dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm that suddenly ruptured.

[3] My mother died of a ruptured thoracic aneurysm. She is buried with my father at Port Hudson National Cemetery.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2025.