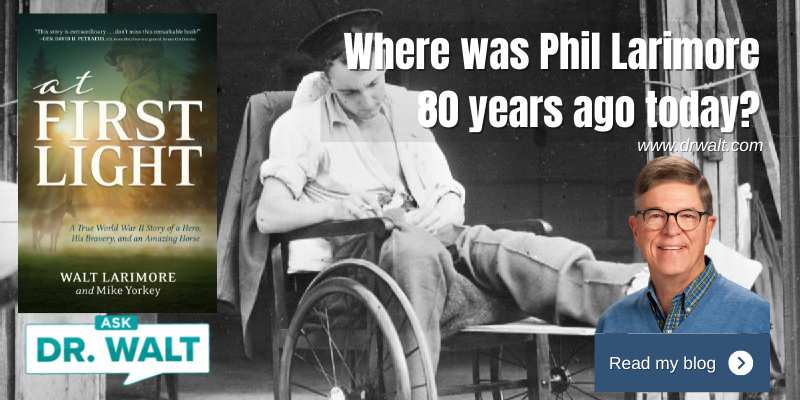

November 15, 1944 – Dad and Audie Murphy recover together

November 15, 2024

Today, on our 51st Wedding Anniversary, can we share our story with you?

November 17, 2024November 16, 1944 – Dad, Audie Murphy, the nurses they admired, and the amazing Frances Slanger

The admiration that Phil, Audie, and other wounded soldiers had for their nurses was enormous—and the feeling was mutual.[1]

The next morning, Phil was reading the military newspaper, Stars and Stripes.

He came across an open letter to the frontline men from Lieutenant Frances Slanger, one of the first nurses to come ashore at Normandy.

Assigned to the 45th Field Hospital to aid casualties in the wake of the Allied invasion of France, Frances shared these observations in the Stars and Stripes:

It is 0200, and I have been lying awake for an hour listening to the steady breathing of the other three nurses in the tent, thinking about some of the things we had discussed during the day.

The fire was burning low, and just a few live coals are on the bottom. With the slow feeding of wood and finally coal, a roaring fire is started. I couldn’t help thinking how similar to a human being a fire is. If it is not allowed to run down too low, and if there is a spark of life left in it, it can be nursed back. So can a human being. It is slow. It is gradual. It is done all the time in these field hospitals and other hospitals at the ETO.

We had several articles in different magazines and papers sent in by grateful GIs praising the work of the nurses around the combat zones. Praising us – for what?

We wade ankle-deep in mud – you have to lie in it. We are restricted to our immediate area, a cow pasture or a hay field, but then who is not restricted?

We have a stove and coal. We even have a laundry line in the tent.

The wind is howling, the tent waving precariously, the rain beating down, the guns firing, and me with ta flashlight writing. It all adds up to a feeling of unrealness. Sure we rough it, but in comparison to the way you men are taking it, we can’t complain nor do we feel that bouquets are due us. But you – the men behind the guns, the men driving our tanks, flying our planes, sailing our ships, building bridges – it is to you we doff our helmets. To every GI wearing the American uniform, for you we have the greatest admiration and respect.

Yes, this time we are handing out the bouquets – but after taking care of some of your buddies, comforting them when they are brought in, bloody, dirty with the earth, mud and grime, and most of them so tired. Somebody’s brothers, somebody’s fathers, somebody’s sons, seeing them gradually brought back to life, to consciousness, and their lips separate into a grin when they first welcome you. Usually they say, “hiya babe, Holy Mackerel, an American woman” – or more indiscreetly “How about a kiss?”

These soldiers stay with us but a short time, from ten days to possibly two weeks. We have learned a great deal about our American boy and the stuff he is made of. The wounded do not cry. Their buddies come first. The patience and determination they show, the courage and fortitude they have is sometimes awesome to behold. It is we who are proud of you, a great distinction to see you open your eyes and with that swell American grin, say “Hiya, Babe.”[2]

Hours after writing this letter, Germans shelled the field hospital and Frances Slanger was killed by an

artillery barrage, becoming the only American nurse to die in the European Theater of Operations during

World War II. She was buried in a military cemetery in France, flanked on either side by the fighting men she served.[3]

~~~~~

[1] Larimore, At First Light, 171.

[2] Frances Y. Slanger (born Friedel Yachet Schlanger, 1913 – October 21, 1944) was an American military nurse of Polish Jewish birth. The only American nurse to die due to enemy fire in the European Theater of WWII, she gained wide posthumous recognition for the letter above. She enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps in 1943, and thanks to persistent requests was deployed to Europe in 1944. Assigned to the 45th Field Hospital, she was one of four military nurses to enter Normandy after D-Day. She soon gained recognition for her ability to improvise under pressure and for her compassion towards those in her care.

[3] Larimore, Ibid, 172.

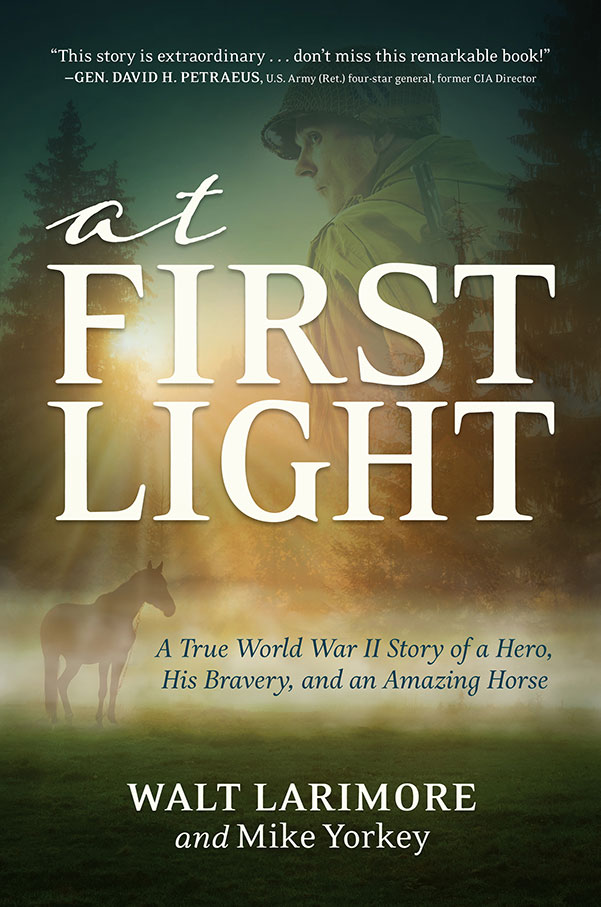

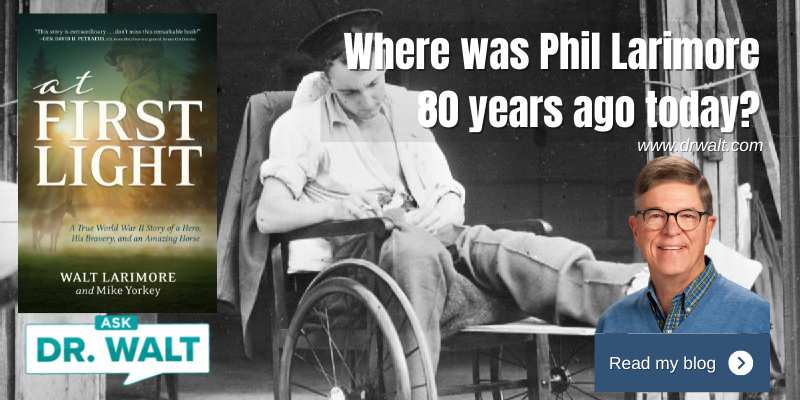

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.