7) Conclusion: Six Questions to Review with Your Family Physician and More Resources for Your Health

November 13, 2024

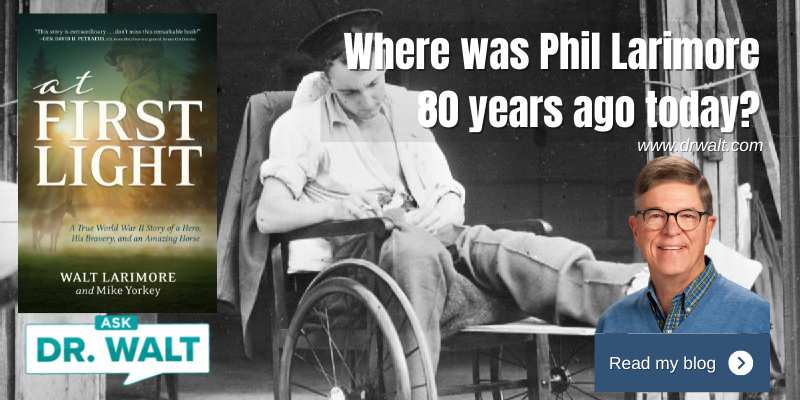

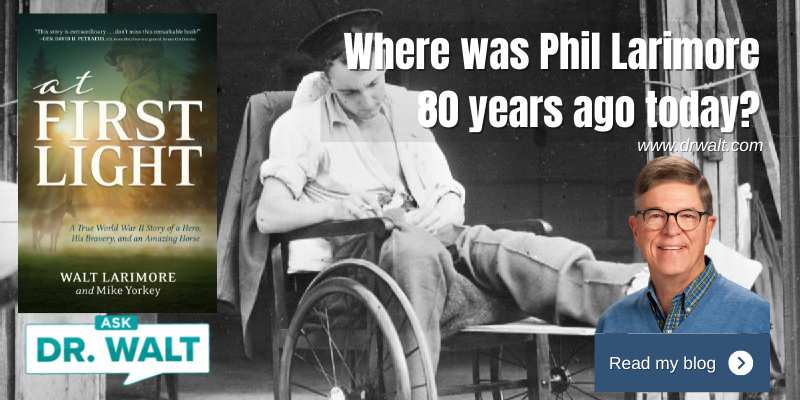

November 15, 1944 – Dad and Audie Murphy recover together

November 15, 2024On November 12, Phil was placed, along with several carloads of wounded troops, on another hospital train. It took almost a full two days for the train to travel 350 miles to arrive in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France on November 14.[1]

Aix-en-Provence, a city of 40,000, had been liberated by the 3rd Infantry Division on August 21, just two months earlier.

Phil was admitted to the Army’s 3rd General Hospital. His first impression of the facility wasn’t just its excellent medical care, but also the delicious French cuisine served to the men.

Phil mistakenly thought his stay would only be a few days, but the doctors caring for him knew he would be of no use to himself or his unit unless he were back literally to 100 percent. Given the amount of injured muscle that needed to heal, he would need plenty of time—likely several weeks, maybe a couple of months—to heal, rehabilitate, and retrain his large leg muscles.

Given the pain and stiffness he felt anytime he tried to stand or walk, it didn’t take him too long to accept his prognosis.

Phil was admitted to a bed next to the nurses’ station in the officer’s surgical ward. Next to him was an officer who looked as young as Phil.

“Whatcha here for?” the young infantry officer asked, with a slow Texan drawl.

Phil explained his wound and asked the young man the same question.

“On twenty-six October, I took a German sniper bullet in the right hip. But I got the sonofabitch right here,” he said, pointing to his forehead, right between his eyes. “Because of the weather, I didn’t get out of the evacuation hospital for three days. It was a damn deep wound, and I came down with gangrene. Guess I’ll be here a while, but I sure want to get back to my guys.”

“What’s your unit?”

“B Company, 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry. Ike was the Battalion Commander back in 1940, long before I joined ’em. How about you?”

“I command an A&P Platoon for the 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry. My first action was Anzio in February ’44.”

“Guess we’ve been fighting together in the 3rd for almost nine months. And you don’t look any older than me. You started as an officer?”

“Yep,” Phil said, “and I was born in January of ’25.”

“Sonofabitch! I’m June of ’25. We’re about the same age.”

“How’d you get in the Army? How long ya been over here?” Phil asked.

The young man laughed. “On my eighteenth birthday, I tried to enlist with the Marines and Paratroopers. Got turned down by both. Said I was too small. That pissed me off. So, I joined the Army. I went through Basic, started out as a private. Landed at Casablanca in February ’43. Trained under Truscott in Algeria, preparing for Sicily. I worked my way up the ranks and made 2nd lieutenant just last month—a battlefield commission. Been in Army hospitals three times, twice for malaria, and another time, just sick as hell. This is my first for a wound.”

“You’ve got a lot more experience than me,” Phil said, smiling. “By the way, I didn’t get your name.”

“Murph’s what my friends call me,” the soldier said, “Audie Murphy.”[2,3]

~~~~~

[1] Larimore, At First Light, 170.

[2] Audie Murphy, called by some the “most decorated U.S. combat soldier in World War II,” earned

twenty-eight awards and medals, including the Medal of Honor. He fought in nine major campaigns and

was wounded three times. After the war, he returned to the U.S. to a hero’s welcome and was featured on

the cover of Life magazine. Hollywood called, and he went on to star in more than forty films and publish

his wartime memoir, To Hell and Back. On the downside, he struggled with post-traumatic stress syndrome

(PTSD), battled depression, slept with a gun under his pillow, and lost a ton of money gambling. He died

in the crash of a private plane in 1971 at the age of forty-six.

[3] Larimore, Ibid, 170-171.

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.