October 28, 1944 – Part Two – Phil defies death at point-blank range

October 28, 2024

October 29, 1944 – Part Two – Phil taken to the OR again and then wrote home

October 29, 2024October 29, 1944 – Part One – The army had a regulation against dying inside an aid station

The next thing Phil knew, one end of his stretcher was strapped to one of his A&P mules, and the other end was carried by Private Vales, who let the mule go first, reining it from behind like he was plowing a field.[1]

Phil drifted in and out of consciousness but woke when they reached the level ground at the spiderweb intersection. Four stretcher-bearers from the forward aid station were waiting to evacuate him. They loaded him into one of the four litter holders mounted on the Jeep, and then they shot off to the battalion aid station, a couple of miles to the rear.

Although his mental status was foggy, Phil, like most injured men from the front, was stunned by how rapidly he was moved. Barely an hour had gone by from the time he’d been shot. Once inside the aid station, Phil knew his chance of survival was excellent.[2] He and his men were convinced the army had a regulation against dying inside an aid station.

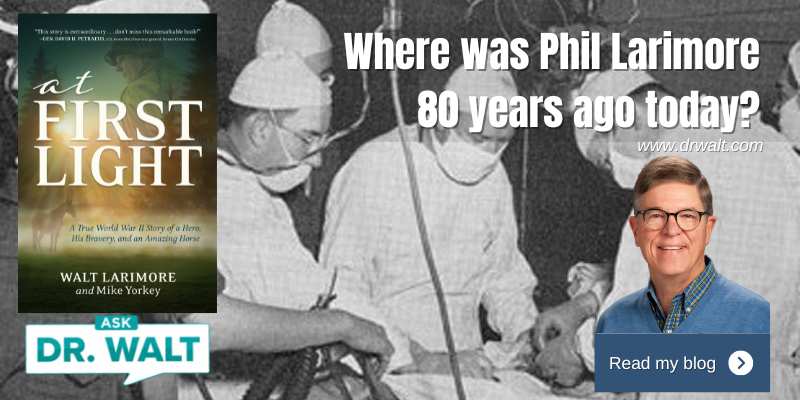

Phil found the light inside the field hospital to be blinding. He was used to total darkness. Besides, the heat from the stove was overbearing, and he thought he was going to faint or vomit. The staff pulled off his heavy field jacket and seated him in a chair. One of the men gave him a drink of water, which felt terrific going down his parched throat. A technical sergeant removed his blood-soaked combat boot and cut the trousers from his right ankle to just below the groin.

For the first time, Phil saw his wound. The bullet had made an ugly, bloody, three-inch gash on the outside of his right thigh, and had left a slightly larger hole on the back of the thigh. The battalion surgeon checked his strength and sensation below the wound.

“You’re one lucky man,” the surgeon, Captain Hilard Kravitz, said. “Doesn’t look like it hit any vital structures. If it’d hit an artery, you’d have lost a lot more blood than you did. I think it missed the bone too, or else you wouldn’t be able to stand. Most importantly, it missed your family jewels—your children will be thankful for that. We’ll move you to a stretcher, Lieutenant, and give you some plasma and another dose of sulfa tablets.”

Phil nodded, wondering what was going to happen next.

Captain Kravitz looked around to be sure no one was looking. “Here, take a dose of my private medicine. It ought to hold you ’till then.” He pulled out a pint bottle of bourbon and let Phil take a long, slow swig.

Phil smacked and licked his lips, shaking his head. “That tasted better than any medicine I’ve ever had. Thanks, Doc.”

The surgeon smiled, took back his flask, and tucked it into his coat pocket. He patted Phil on the back.

As a technical sergeant sprinkled more sulfa powder into each wound and redressed them, Phil heard footsteps behind him. The man attending him sprung up to attention and saluted.

“At ease!”

Phil turned to see his 3rd Battalion Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Neddersen, and tried to stand.

Neddersen put his hand on Phil’s shoulder. “Don’t even think about it, Lieutenant.”

The colonel knelt. “Hell of a job out there, you and Vales getting as much ammo to those guys as you did. They would’ve been wiped out without your work. Well done. But that’s what I’vecome to expect of you.”

“And so have I,” said a gravelly voice behind him. Phil turned to see Colonel McGarr. “They tell us it’s just a flesh wound. So you get to the hospital, get taken care of, and get back here. We need you back, Larimore, but not until you’re 100 percent. You understand me?”

“Yes, sir. Just hold my position at the platoon if you would.”

Colonel McGarr’s eyes softened. “You know we can’t do that, Lieutenant. But we’ve had it in our minds for some time to get you out of our command staff and into commanding a company. You’re young, but you’ve got more experience and wisdom than most. So, you just do your job—get well. And we’ll absolutely guarantee you a job with us when you get back. You hear?”

“Yes, sir.”

As the colonels stood, Phil saluted, and they immediately returned his salute. They turned and quickly left.

God, I love those men, Phil thought. Their confidence in him lifted his spirits and was like a balm to his wounds.

TO BE CONTINUED LATER TODAY.

~~~~~

[1] Larimore, At First Light, 164.

[2] In World War I, approximately four out of every 100 wounded men could expect to survive; in World War II, the rate improved to 50 out of 100. A soldier who received treatment within an hour of being seriously wounded had a 90 percent chance of recovery.

[3] Ibid, 164-166.

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.