“Ask Dr. Walt” in Today’s Christian Living “Laughter is the Best Prescription” (Part 2)

August 14, 2024

August 15, 1944 — The southern France D-Day (Part 1)

August 15, 2024OPERATION DRAGOON [the southern France D-Day], originally called ANVIL, had first been intended as a diversion during OPERATION OVERLORD [the D-Day at Normandy] to occupy eighteen German divisions south of the Loire in Army Group G. Shipping shortages and delays in capturing Rome forced a postponement until long after the Normandy landings, yet the Americans remained keen on the operation.[1]

Marseille and Toulon would provide ports at a time when dozens of U.S. Army divisions were stuck at home for lack of dockage in Normandy. DRAGOON could discomfit the enemy with the thrust up the Valley, an invasion route since Caesar’s wars, and it would profitably employ several veteran French divisions now fighting in Italy; with a mother country still to liberate, De Gaulle had forbidden those forces to venture beyond the river Arno.

“France,” Eisenhower told the British, “is the decisive theater.”

The British disagreed, politely at first, then adamantly.

Churchill warned Roosevelt of a “bleak and sterile” invasion through Provence, followed by “very great hazards, difficulties, and delays” in slogging up the Rhône. Marseille lay 400 miles from Paris, and a battle there was unlikely to influence the fight for northern France; simply reaching Lyon, he predicted, would take three months.

Pulling the U.S. VI Corps and the French division from Italy “is not acceptable to us,” the British military chiefs added. Instead, why not blast across the Po Valley in northern Italy, swing east with help from an amphibious landing at Trieste, and drive through the so-called Ljubljana Gap in Slovenia to reach Austria, and the Danube valley?

The allied commander in Italy, Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, promised to Churchill that he intended to “eliminate the German forces in Italy. I shall them have nothing to prevent me from marching on Vienna.” This thrust of “a dagger under the armpit,” as the prime minister called it, might even force Hitler to abandon France in order to shore up is southeastern front.

Back and forth the argument flew it’s like a shuttlecock. … “Ike said no, continued saying no all afternoon, and ended up saying no in every form of the English language at his command,” Harry Butcher wrote.

Britain would win the war while losing this battle and most other battles waged against the Americans hence forth. … Now, [Churchill] would return to the Villa Rivalta, his hostel above Naples Bay, and pack for a C-47 flight to Corsica, his own staging area for the invasion.[2]

~~~~~

On August 14th the invasion force consisting of the VI Corps. with the US 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions.[3]

~~~~~

At about 1900 on August 14th off the west coast of Corsica, the ‘Dragoon’ convoys made their rendezvous and turned toward their objectives on the French Rivieria. Before the main assault on the … coastline, plans to isolate the invasion area by commando forces on the flanks went into operation.[4]

~~~~~

The various convoys … then sailed northward that night toward the transport areas, where the troops would disembark and begin their run-ins to the beaches in the landing craft.[5]

~~~~~

On the evening of August 14, allied naval guns pounded the flanks of the landing area.[6]

~~~~~

PHASE III (Operation ‘Yokum’) was to begin one hour after the conclusion of ‘Nutmeg’ (1800 hours D-minus-1) and last until H-Hour. Its main task was to inflict maximum destruction on enemy coastal and beach defences, using all available forces. These included twelve heavy bomber groups, plus medium and fighter bombers. The latter were to attack coastal batteries, while the heavy bombers were to strike at assault beaches to flatten underwater obstacles and enemy strongpoints.[7]

~~~~~

[1] Atkinson, The Last Day of Battle, 192.

[2] Ibid, 192-195.

[3] Sgt. James Dunigan III. History of the U.S. 30th Infantry Regiment.

[4] Turner, 35.

[5] Heefner. Dogface Soldier, 190-191.

[6] Champagne, 78.

[7] Turner, 34.

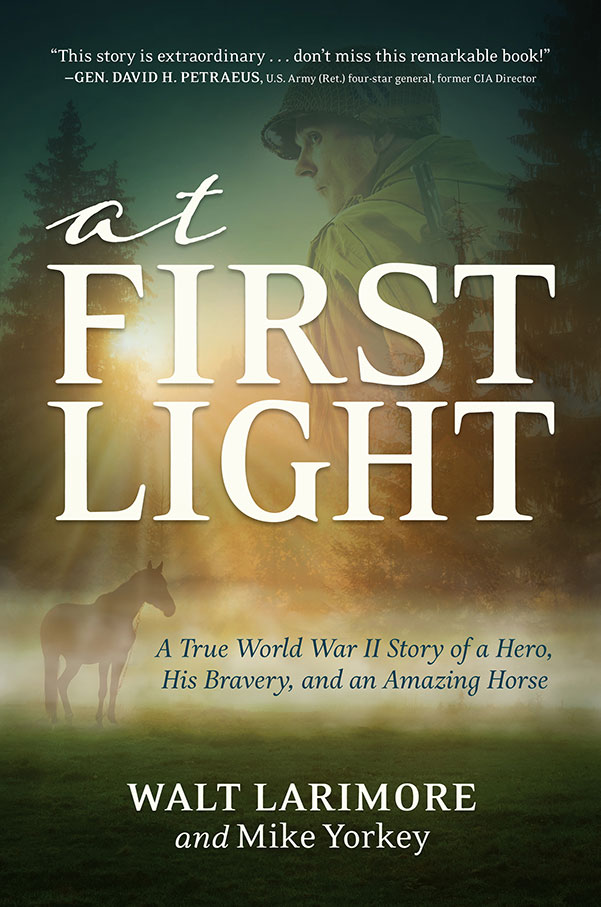

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.