August 27, 1944 – Dad and his best friend create a life-long memory fighting together as one

August 27, 2024

August 29, 1944 – One of my Dad’s most memorable equestrian missions of WWII – Part 1

August 28, 2024“There’s nothing I don’t know about war. The stench of it … War is a terrible thing.” Don McCullin, award-winning war photographer.[1]

The next major engagement of the invasion of southern France would become known as the “Battle of the Montélimar Square,” an area one hundred miles north of the coastal city of Marseille and along the German route of withdrawal.

Before the war, Montélimar’s claim to fame was its reputation as the center of production for nougat, a sticky, tooth-breaking confection popular with French children.

But as Allied forces advanced quickly, the German Nineteenth Army had no choice but to pass through Montélimar and continue in a northerly direction through a steep gorge where the Rhône River, railroad tracks, and the Route Nationale 7 highway barely had room to squeeze through together—a fact not lost on General Truscott and his military planners.

Units from the 3rd and 36th Divisions raced ahead to strategically occupy the dominating heights on both sides of the gorge just north of Montélimar.

At first light, the American forces on the gorge’s east ridge were gripped by the scene below them. Within easy 60-mm mortar range was a German convoy with more than 2,000 vehicles—heavy cargo trucks, half-tracks, numerous requisitioned French sedans—jammed bumper-to-bumper and joined by 1,000 horses pulling carts or trailing behind motor vehicles, most of them stolen from the French.

Scattered among them were several thousand German soldiers, including over a thousand on foot—all in frantic retreat from the 3rd Division rapidly approaching from the south.

As the German convoy’s lead elements passed through the narrow canyon at 0630 hours, American artillery unleashed a furious barrage. This was like shooting fish in a barrel. Thirty-three ammunition trucks blew up, setting the rest of the convoy on fire, since many of the trucks had been topped off with fuel.

A ten-mile stretch of the valley was quickly obscured by the smoking hulks of burning vehicles, dead men, and horse carcasses, not to mention hundreds of artillery pieces and masses of small arms, automatic weapons, ammunition, and other equipment, which created a massive roadblock of wrecked enemy vehicles.

The surviving drivers and personnel abandoned their vehicles and raced for the relative safety of the Rhône River.

Then the first of three German trains raced up the valley. The 133rd Field Artillery Battalion scored two direct hits on the lead train of fifty-five cars. Two following trains—blocked by the wreckage—were also hit, including six massive railroad guns. Four were the dreaded “Anzio Annies.” To the men’s disbelief, they discovered two even larger railway guns that were, until then, unknown to the Allies. These were “Annie’s Big Sisters” [131-foot-long cannons with a bore of 4.6 inches, and could fire shells up to 35 miles].

After sunrise, Allied fighter bombers poured in at treetop level, inflicting massive damage with their cannons, rockets, and 500- and 1,000-pound bombs on the already hard-pressed enemy.

When General Truscott was flown over the valley in a Piper Cub to examine the battlefield, he told others that the “sight and smell of this section is an experience I have no wish to repeat.”[2]

The horror of the morning battle just north of Montelimar, set the stage for one of Phil’s most memorable and exciting afternoons of the war.

~~~~~

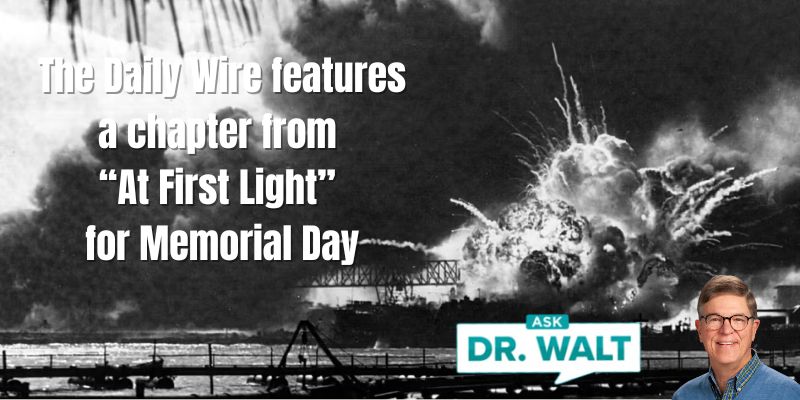

[1] Larimore, At First LIght, 130.

[2] Ibid, 130-131.

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.