August 28, 1944 – The horrors of Montelimar for the retreating Germans

August 28, 2024

August 30, 1944 – One of my Dad’s most memorable equestrian missions of WWII – Part 2

August 29, 2024On the afternoon of August 28, 1944, on the outskirts of Montélimar, Phil was called over to his commander’s jeep. Col. Lionel McGarr commanded the 30th Infantry Regiment. Like Phil, he was an equestrian. Unbeknownst to Phil, Col. McGarr was ready to give him what would become one of his most memorable assignments of the war.[1]

“Lieutenant,” the colonel barked, pointing at a map of the area, “I have an assignment for you and a few of your men.”

He pointed on the map to the gorge just north of Montélimar. “Along the N-7 here, I’m told the devastation to the enemy is spectacular. A lot of horses were killed and wounded, while many others escaped.”

The colonel looked up at him. “You’re a horseman, Lieutenant. I want you to handpick a squad of other horsemen, establish a corral, and round up as many of the healthy ones as possible. Put down the others.”

Phil chose a few men from his battalion—all farm boys—and they drove up the N-7 in Jeeps. His buddy Ross Calvert joined them. Just north of the city, they ran into prisoners belonging to the German Nineteenth Army, accompanied by GIs with Tommy guns. Lines of German soldiers, their eyes glazed over and their heads hanging low, streamed by as they headed toward the prisoner cages being set up in Montélimar.

Then Phil and his men passed a small farmhouse with a sizeable courtyard surrounded by a stone fence. Inside the yard were a horse trough and a hand pump. Phil turned to two of the privates.

“You men secure this home. Get any hay or feed you can from the barn or neighbors, fill the water trough, and then wait here at the gate. We’ll send back any horses we can.”

As Phil and Ross moved further up the road in their Jeep, they encountered overwhelming carnage. Charred tanks and myriad burning vehicles were scattered bumper-to-bumper and side by side in long, disorganized columns. Besides the crackling sound of fires, the air was hushed, except for the buzzing of countless feasting flies. The vultures not already feasting on flesh circled overhead and cast shadows on the corpses. The men were silent in their thoughts about the horror they saw.

They came upon American soldiers from other units walking up the roadway of ruin, the avenue of annihilation. As he tried to take in the degree of devastation, Phil said to Ross, “This looks like a highway to hell.”

Along the road and in the fields, they passed the bodies of hundreds of dead Germans, most of them fire-blackened, who had been cut down while trying to escape. The bodies of dead soldiers who hadn’t been burned to a crisp were starting to swell in the hot August sun, their mouths agape, filled with flies.

Phil and Ross covered their faces with bandanas because of the horrible, fetid smells. The entire length of the panorama of destruction was worsened by the outrageous odor of bloated horses, burning wood, scorched metal, and roasted flesh assailing the men’s nostrils. They quickly named the road the “Avenue of Stenches.”

Phil couldn’t help noticing how other soldiers were taking advantage of the spoils of war. This was Phil’s first experience with widespread looting, Scores of American soldiers stopped to grab Lugers, watches, knives, Nazi patches, and jewelry from the dead bodies. Any pockets containing money and liquor were a bonus.

Also astounding was the number of dead horses littering the roads and shoulders. Phil could tell that most had been stolen from the French farmers because the tack was simple, and the horses were untrimmed. On the other hand, German horses had been groomed with hooves and tails trimmed, as though for a parade, and had impressive tack with highly polished leather and brass rivets that shone brightly.

He was surprised the German Army relied on so many horses to pull, and his men were astonished to learn the German Army was still a horse-drawn military force in many ways, having more horses in an infantry division than they had men for pulling carts, wagons, and artillery pieces.[2]

It wasn’t too long before Phil and his men ran into scared and injured horses that had survived the devastating bombardment that nearly wiped out the convoy. These skittish and traumatized horses needed attention, which he and his fellow warhorsemen were willing to provide.

Phil had been at war about six months, and he was now well acquainted with the sight and sounds of horribly wounded soldiers, as well as the smell and spectacle of dead men. Still, the sight of these shocked and damaged animals affected him more profoundly than he expected.

He was reminded that the butchery and bloodbath of war inadvertently swept over far too many innocents.

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART 2 AND PART 3.

~~~~~

[1] Larimore, At First LIght, 131.

[2] Horse-drawn transportation was important for Germany as the country was relatively lacking in natural oil resources. Infantry and horse-drawn artillery formed the bulk of the German Army throughout the war. Only one-fifth of the Army belonged to mobile Panzer and mechanized divisions. Each German Infantry division employed thousands of horses and thousands of men taking care of them. The German Army entered WWII with 514,000 horses, and over the course of the war, employed 2.75 million horses and mules in total, averaging 1.1 million horses at any time. Most were used by foot Infantry and horse-drawn artillery troops.

[3] Larimore, At First LIght, 131-133.

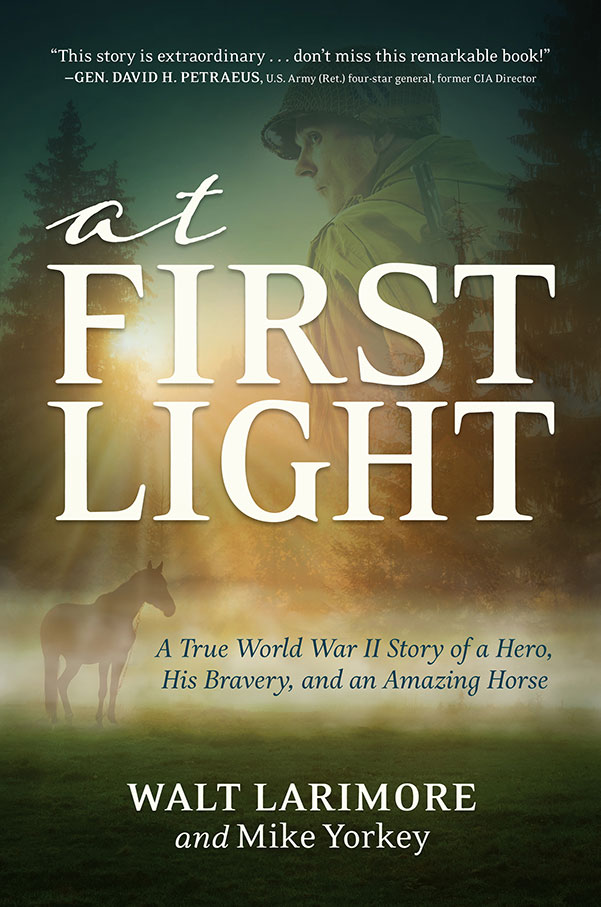

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.