August 1, 1944 — A last-minute name change for the upcoming D-Day

August 1, 2024

List of my July WWII Blogs on “Where were my Dad and his men 80 years ago today?”

August 3, 2024Those who fought and suffered in Italy—that “tough old gut,” as Ernie Pyle called it—were left to extract from the bad time what redemption they could. “Few of us can ever conjure up any truly fond memories of the Italian campaign,” Pyle wrote in Brave Men in late 1944. “The enemy had been hard, and so had the elements. … There was little solace for those who had suffered, and none at all for those who had died, in trying to rationalize about why things happed as they did.”[1]

Pyle continued:

I looked at it this way—if by having only a small army in Italy we had been able to build up more powerful forces in England, and if by sacrificing a few thousand lives that winter we would save a half million lives in Europe—if those things were true, then it was best as it was. I wasn’t sure they were true. I only knew I had to look at it that way or else I couldn’t bear to think of it at all.[1]

Faith and imagination were required to elevate the Italian campaign, to see as the poet Richard Wilbur, a veteran of Cassino and Anzio, saw: “the dreamt land / Toward which all hungers leap, all pleasures pass.”[1]

Even Pyle, who knew better than most that “war isn’t romantic to the people in it,” sensed the sublime in moments “of overpowering beauty, of the surge of a marching world, of the relentlessness of our fate.”[1]

George Biddle had found that in “misery, destruction, frustration, and death,” certain annealed qualities seemed “to give war its justification, meaning, romance, and beauty. The qualities of valor, sacrifice, discipline, a sense of duty.”[1]

Even Mauldin, that flinty-eyed skeptic, would concede, “I stopped regarding the war as a show to help my career. I felt a seriousness of purpose, I felt it in my bones.”[1]

A medic who had landed at Salerno later wrote his wife, “This is something that is born deep inside us, when we come to know why we are here, when we have learned how very important it was that we did leave you and all we love.”[1]

Somewhere north of Rome, Glenn Gray wrote in his diary: “I watched a full moon sail through a cloudy sky … I felt again the aching beauty of this incomparable land. I remembered everything that I had ever been and was. It was painful and glorious.”[2]

Another day passed, and another night. The circling stars glided on their courses. The poets and dreamers again struck their tents and shouldered their rifles to begin that long, last march.[2]

[1] Atkinson. The Day of the Battle, 587.

[2] Atkinson. The Day of the Battle, 588.

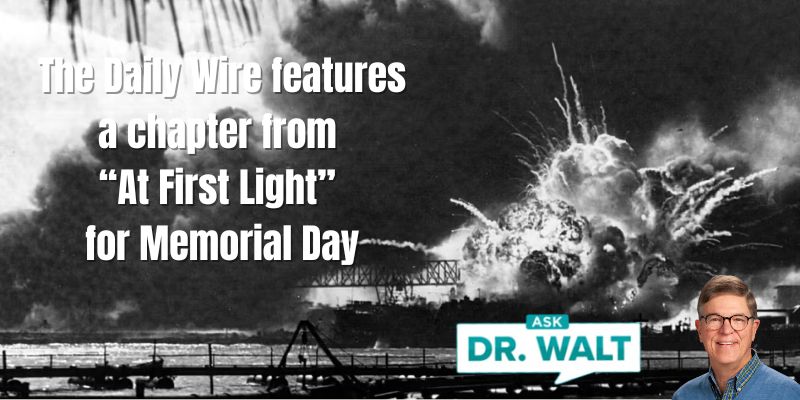

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.