List of my March Blogs on “Where was Dad 80 years ago today?”

April 2, 2024

“Ask Dr. Walt” in Today’s Christian Living “Red Rice Yeast for High Cholesterol?” (Part 1 of 7)

April 3, 2024War correspondent, Ernie Pyle, wrote, “American infantry fighters on the Fifth army beachhead were having a welcome breathing spell when I dropped around to leave my calling card.”[1]

Pyle continued in a piece titled, “Soldier In Foxhole Solves His Own Insomnia Problem:”[1]

There’s nothing that suits me better than a breathing spell, so I stayed and passed the time of day. My hosts were a company of the 179th infantry. They had just come out of the lines that morning, and had dug in on a little slope three miles back of the perimeter. The sun shone for a change, and we lay around on the ground talking and soaking up the warmth.

Every few minutes a shell would smack a few hundred yards away. Our own heavy artillery made such a booming that once in a while we had to wait a few seconds in order to be heard. Planes were high overhead constantly, and now and then you could hear the ratta-tat-tat of machinegunning up there out of sight in the blue, and thin white vapor trails from the planes.

That scene may sound very warlike to .you, but so great is the contrast between the actual lines and even a little way back, that it was actually a setting of great calm.

This company had been in the front lines for more than a week. They were back to rest for a few days. There hadn’t been any real attacks from either side during their latest stay in the lines, and yet there wasn’t a moment of the day or night when they were not in great danger.

Up there in the front our men lie in shallow foxholes. The Germans arc a few hundred yards on beyond them, also dug into foxholes, and buttressed in every farmhouse with machine-gun nests. The ground on the perimeter line slopes slightly down toward us—just enough to give the Germans the advantage of observation.

There are no trees or hillocks or anything up there for protection. You just lie in your foxhole from dawn till dark. If you raise your head a few feet, you a rain of machine-gun bullets.

During these periods of comparative quiet on the front, it’s mostly a matter of watchful waiting on both sides. That doesn’t mean that nothing happens, for at night we send out patrols to feel out the German positions, and the Germans try to get behind our lines. And day and night the men on both sides are splattered with artillery, although we splatter a great deal more of it nowadays than the Germans do.

Back on the lines, where the ground is a little higher, men can dig deep into the ground and make comfortable dugouts which also give protection from shell fragments But on the perimeter line the ground is so marshy that water rises in the bottom of a hole only eighteen inches deep. Hence there are many artillery wounds.

When a man is wounded, he just has to lie there and suffer till dark. Occasionally, when one is wounded badly, he’ll call out and the word is passed back and the medics make a dash for him. But usually he just has to treat himself and wait till dark.

For more than a week these boys lay in water in their foxholes, able to move or stretch themselves only at night. In addition to water seeping up from below, it rained from above all the time. It was cold, too, and of a morning new snow would glisten on the hills ahead.

Dry socks were sent up about every other day, but that didn’t mean much. Dry socks are wet in five minutes after you put them on.

Wet feet and cold feet together eventually result in that hideous wartime occupational disease known as trench-foot. Both sides have it up here, as well as in the mountains around Cassino.

The boys have learned to change their socks very quickly, and get their shoes back on, because once your feet are freed of shoes they swell so much in five minutes you can’t get the shoes back on.

Extreme cases were evacuated at night. But only the worst ones. When the company came out of the lines some of the men could hardly walk, but they had stayed it out.

Living like this, it is almost impossible to sleep. You finally get to the point where you can’t stay awake, and yet you can’t sleep lying in cold water. It’s like the irresistible force meeting the immovable object.

I heard of one boy who tried to sleep sitting up in his foxhole, but kept falling over into the water and waking up. He finally solved his dilemma. There was a fallen tree alongside his foxhole, so he tied some rope around his chest and tied the other end to the tree trunk, so that it held him up while he slept.

Living as these boys do, it seems to me they should all be down with pneumonia inside of a week. But cases of serious illness are fairly rare.

Maybe the answer lies over matter. I asked one sergeant if a lot of men didn’t get sick from exposure up there and have to be sent back. I’ll always remember his answer. He said, “No, not many. You just don’t get sick—that’s all.”

~~~~~

[1] Ernie Pyle. With Fifth Army Beachhead Forces in Italy. (By Wireless). The Commercial Appeal, Memphis. News Clipping in small brown scrapbook with heavily embossed front.

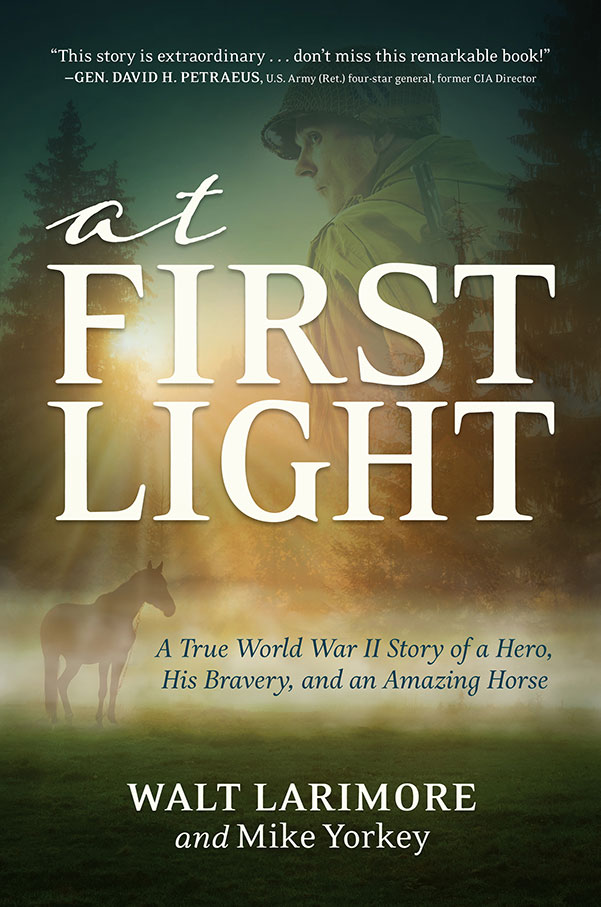

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.