Praying with patients in clinical care (ICMDA Webinar – 1 of 5)

April 17, 2024

April 18, 1944 — Army finally comes thru with a practical front line stove and candles

April 18, 2024War correspondent, Ernie Pyle, wrote, “In addition to its regular job of furnishing food and clothing to the troops, the Quartermaster Corps of the Fifth Army beachhead runs the bakery, a laundry for the hospitals, a big salvage depot of old equipment and the military cemetery.”[1]

Pyle continued:

Hospital pillows and sheets are the only laundry done on the beachhead by the Amy. Everything else the individual soldiers either wash themselves or hire Italian farm women to do. People like me just go dirty and enjoy it.

The army laundry is on several big mobile trucks hidden under the sharp slope of a low hill. They are so well camouflaged that a photographer who went out to take some pictures came away without any—he said the pictures wouldn’t show anything.

This laundry can turn out 3,000 pieces in 10 hours of work. About 80 men are in the laundry platoon. They are dug in and live fairly nicely.

Laundrymen have been killed in other campaigns, but so far they’ve escaped up here. Their worst disaster was that the little shower-bath building they built for themselves has been destroyed three times by “ducks” which got out of control when their brakes failed and came plunging over the bluff.

Continuing with “ducks” for a moment, in one company all these amphibian trucks have been given names. The men have stenciled the names on the sides in big white letters, and every name starts with “A.” There are such names as “Avalon” and “Ark Royal.” Some bitter soul named his duck “Atabrine,” and an even bitterer one called his “Assinine”—misspelling the word, with two s’s, just to rub it in.

Our salvage dump is a touching place. Every day five or six truckloads of assorted personal stuff are dumped on the ground in an open space near town. It is mostly the clothing of soldiers who have been killed or wounded. It is mud-caked and often bloody.

Negro soldiers sort it out and classify it for cleaning. They poke through the great heap, picking out shoes of the same size to put together, picking out knives and forks and leggings and underwear and cans of C ration and goggles and canteens and sorting them into different piles.

Everything that can be used again is returned to the issue bins as it is or sent to Naples for repair.

They find many odd things in the pockets of the discarded clothing. And they have to watch out, for the pockets sometimes carry hand grenades. § You feel sad and tight-lipped when you look closely through the great pile. Inanimate things can sometimes speak so forcefully—a helmet with a bullet hole in the front, one overshoe all ripped with shrapnel, a portable typewriter pitifully and irreparably smashed, a pair of muddy pants, bloody and with one leg gone.

The cemetery is neat and its rows of wooden crosses are very white—and it is very big. All the American dead of the beachhead are buried in one cemetery.

Trucks bring the bodies in daily. Italian civilians and American soldiers dig the graves. They try to keep ahead by 50 graves or so. Only once or twice have they been swamped. Each man is buried in a white mattress cover.

The graves are five feet deep and close together: A little separate section is for the Germans, and there are more, than 300 in it. We have only a few American dead who are unidentified. Meticulous records are kept on everything.

They had to hunt quite a while to find a knoll high enough on this Anzio beachhead so that they wouldn’t hit water five feet down. . The men who keep the graves live beneath ground themselves, in nearby dugouts.

Even the dead are not safe on the beachhead, nor the living who care for the dead. Many times German shells have landed in the cemetery. Men have been wounded as they dug graves. Once a body was uprooted and had to be reburied.

The inevitable pet dog barks and scampers around the area, not realizing where he is. The soldiers say at times he has kept them from going nuts.[1]

~~~~~

At a salvage dump outside Nettuno, quartermasters each day picked up through truckloads of clothing and kit from soldiers killed or wounded—sorting heaps of shoes, goggles, forks, canteens, bloody leggings.

“It was best not to look too closely at the great pile,” advised Ernie Pyle. “Inanimate things can sometimes speak so forcefully.”

Nearby, more trucks hauled the day’s dead to a field sprouting white crosses and six-pointed stars. Grave diggers halted their poker game—the trestle-and-plywood table, in a bunker built from rail ties, could seat seven players—and hurried through their offices. Like the rest of the Bitchhead, the cemetery frequently came under fire, so burial services were short and often nocturnal. Grief was a brief. The diggers tried to stay fifty holes ahead of demand, but keeping pace could be difficult when shells disinterred the dead, who required reburying.

Life went on, miserable and infinitely precious. “Remember,” a gunner wrote in a note to himself, “it can never be as bad as it was at Anzio.”

It got worse. [2]

[1] Ernie Pyle. With Fifth Army Beachhead Forces in Italy. (By Wireless). Even the Dead are not Safe on the Anzio Beachhead The Commercial Appeal, Memphis. News Clipping.

[2] Atkinson, The Day of Battle, 415.

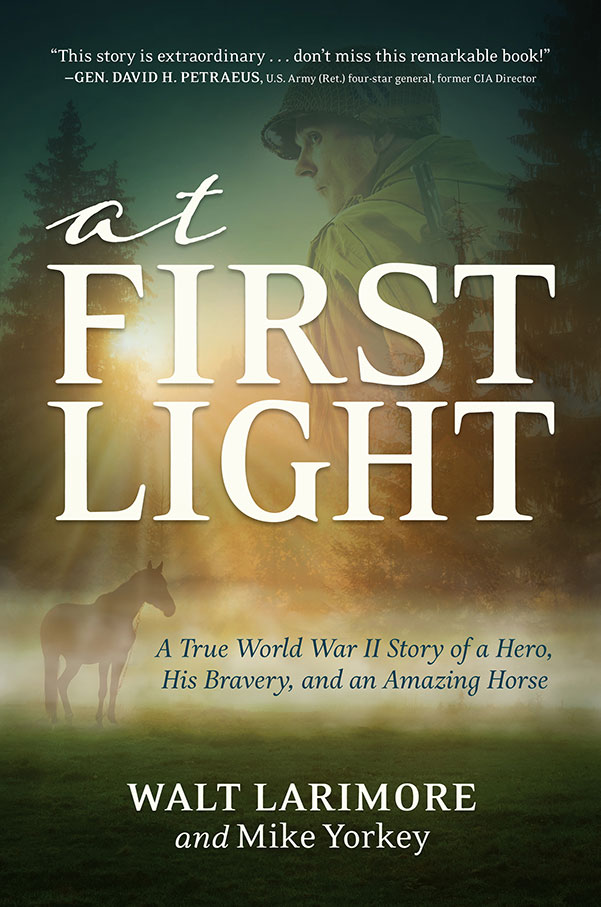

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.