March 4, 1944 – Letters home from Anzio

March 4, 2024

“Vaccine News You Can Use” for Family Physicians – Winter 2024

March 6, 2024From the beginning of March, the forward positions at Anzio beachhead were stabilized and remained practically unchanged until the breakthrough in May. Conditions at Anzio resembled the quiescent periods of trench warfare on the Western Front during World War I.

The great bulk of VI Corps casualties were caused by enemy air raids and especially by enemy artillery fire.

The narrow confines of the beachhead made it peculiarly vulnerable to enemy artillery, which ranged from 88-mm. guns up to giant 290-mm. railroad guns. One of the latter was popularly known as the “Anzio Express,” also as “Anzio Annie.”

These big guns, not to be confused with the smaller railroad guns which the Germans had employed during February, were first reported in action on 24 March.

During March, 83 percent of the combat casualties of the 3rd Division were caused by shell fragments, although the division occupied a long sector of the forward line until the end of the month.

VI Corps’ highly centralized fire control center carried out a systematic program of counterbattery firing to combat enemy artillery. Its efforts became more effective in April with the arrival at the beachhead of heavier artillery weapons–8-inch guns and howitzers and 240-mm. howitzers.

Smoke generators, used to create an artificial fog behind the lines, helped to reduce the accuracy of enemy artillery and of bombing; but there was only one effective answer to the problem of security from the constant pounding of enemy shells and bombs: that was to go underground.

The whole beachhead area became a honeycomb of trenches, fox holes, and dugouts as the men burrowed into the sandy ground. Bulldozers dug pits for guns and vehicles and pushed up tons of earth around the neatly stacked piles of gasoline cans and ammunition which were located in every open field in the rear areas.

During the rainy winter months the process of digging in was hampered by the proximity of the ground water to the surface. Fox holes and dugouts quickly filled with water. With the arrival of spring, warm and sunny days dried up the ground and it became possible to construct a dugout without striking water. Viewed from the air the beachhead created the illusion that thousands of giant moles had been at work.

In the American hospital area near Anzio, the 36th Engineers set to work excavating foundations three and one-half feet deep for hospital tents; the sides of each tent were further strengthened by sandbag walls. Even with these improvements, the hospital area remained one of the more dangerous spots on the beachhead.

No soldier who was at Anzio will forget the work of the doctors, nurses, and aid men who served with them. When the shells were coming over or the air raid siren signalled a red alert others could seek shelter; the doctor performing an operation or the nurse tending a patient had no choice but to continue in the performance of his or her task.

A measure of their courage and willingness to sacrifice themselves for their patients is indicated by the losses suffered by medical personnel at the beachhead. Ninety-two were reported killed in action (including 6 nurses), 387 wounded, 19 captured, and 60 reported missing in action.

To counteract the debilitating effects of static warfare, General Truscott not only conducted a vigorous training program but also endeavored to give his men as much rest and recreation as possible when they were out of the line.

Owing to the open nature of most of the beachhead terrain, troops in forward areas usually stayed underground during the day; at night combat patrols probed deep into the enemy lines, and occasionally a company or battalion launched an attack to take prisoners or capture or destroy a strategic group of buildings.

Recreation and training facilities were limited by the lack of a safe rear area. The 1st Armored Division built two underground theaters, each capable of holding over two hundred men. Each division set up small recreation and bath units; at the latter, the men could obtain a complete change of clothing.

On the coast below Nettuno the 3rd Division established a large rest camp where men could combine training with opportunities for swimming, going to the movies, and writing letters.

Every four days VI Corps sent 750 men by LST to the Fifth Army rest camp at Caserta. Troops at the beachhead were given priority on mail, Post Exchange supplies, and recreation equipment.

The quality of their food also improved. During February, rear-area as well as front-line troops lived almost exclusively on C and K rations; by March calmer seas and lessened enemy activity permitted Liberty ships to bring in fresh meat and a high percentage of B rations.

Where organized recreation was impossible, men provided their own amusement. Horseshoes were in great demand, and volley ball and even baseball games were played close to the fighting front. When enemy shells started coming in, the men ducked for cover and then calmly returned to their games.

A few troops had their own chicken pens; others, less fortunate, dickered with the few remaining Italian farmers for eggs. Patrols for chickens and livestock were as carefully planned as patrols against the enemy.

To help pass the long hours in dugouts men improvised radio sets on which they could listen to the Fifth Army Expeditionary Station and also to Axis propaganda broadcasts. “Sally,” the German radio entertainer, was as well known to them as the “Anzio Express.” They enjoyed her throaty voice and her selections of the latest American popular music; they laughed at her crude propaganda and that of her partner “George,” just as they laughed at the German propaganda leaflets which they collected for souvenirs.

German efforts to sow discontent among the Allied troops at the beachhead were singularly unsuccessful. They merely supplied an additional source of entertainment.

It was easy for a replacement arriving at the beachhead on one of the occasionally beautiful March days, to gain the impression that, despite all the evidence of destruction around the tiny harbor, Anzio was a relatively safe spot. Even the occasional white plume of water, rising as an enemy shell plunged into the calm bay, had an impersonal air about it.

Men worked at the docks unloading LST’s or LCT’s, drivers of DUKW’s churned their vehicles out across the bay toward the Liberty ships outside the harbor, antiaircraft crews lolled by their guns, and a few men swam along the shore below the battered villas.

But the apparent unconcern of the men was deceptive.

The terrific tension under which they had lived during the critical days of February had eased somewhat, but some measure of it was still there.

The next shell to whistle over the beachhead might well land in the hold of a ship or obliterate a truck driving through the streets of Anzio or Nettuno.

At dusk the feeling of tension increased; men around the harbor kept an eye on the end of the jetty, where the raising of a flag gave warning of another air attack.

Although the enemy abandoned daylight raids after the costly attacks of February, anywhere from one to half a dozen attacks were made every night, and the enemy shelling, sporadic during daylight hours, substantially increased after dark.

One night at Anzio dispelled all illusions of security. The battle of the beachhead remained a grim and deadly struggle to the end.

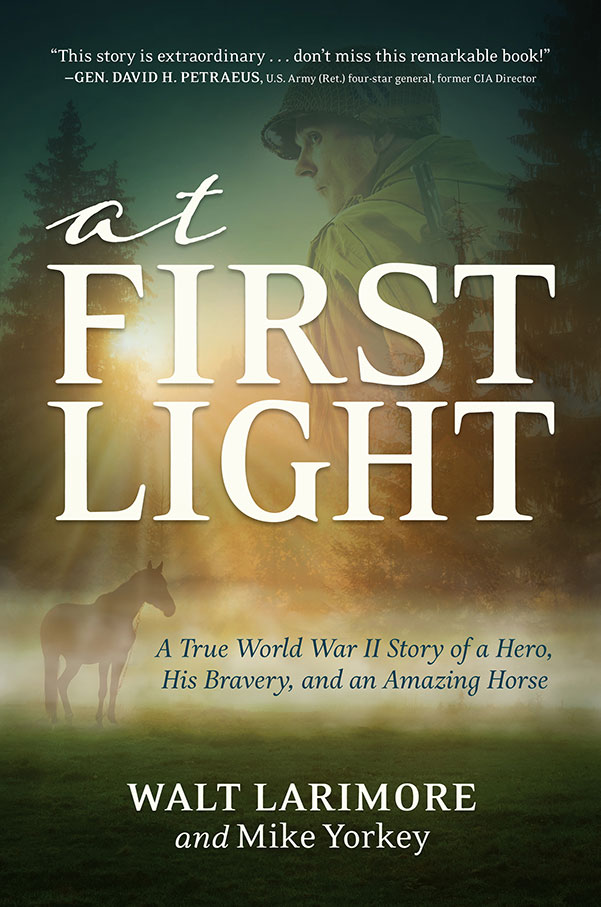

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.