March 9, 1944 – Letters home from the Anzio beachhead

March 9, 2024

Should one pray for healing only versus seeking medical care only?

March 10, 2024The Anzio Beachhead quieted down and took on the characteristics of garrison life. Because Phil and his men spent a lot of time in wet trenches, many came down with severe colds, including Phil.

He wrote to his parents:

There isn’t much going on now, and any thing that is going on I can’t tell you about it so I guess I’ll jut have to wait untill(sic) I get some mail from you so I will know what you are wanting to know about.

My work goes on every night just the same. The one thing about it, there is never a dull moment. Always something goes on to make you keep on guard too.

I have been sick the last day or so, not able to hold my food down, but last night the Major (Bn Commander) made me go to bed right after supper and the doctor came up to see me. He made me drink something and gave a fist full of pills.

This morning I fell much better and I think I’ll be ok now. It seems to happen to every one once in a while.

Mom I sure would like to have home made candy, tell Eloise I’d like to have some like that she sent me for Christmas.

Well my paper has run out so I will have to also.

With all my love

Your son

Philip

The next day Phil’s condition worsened, and he developed a high fever with chills and sweats, a severe headache, and crippling fatigue, all accompanied by worsening nausea and vomiting. One of the frontline medics quickly sent him to a field hospital.

He arrived with a boiling temperature of 105 degrees and in delirium. With a rapid treatment of aspirin, intravenous (IV) fluids, and cold packs, his temperature finally subsided. He awoke, groggy, to see a nurse from the Army Nurse Corps (ANC). She looked exhausted in her fatigues but took his hand in hers. Phil thought she was heaven sent.

“You’re on the mend, soldier,” she said softly, with a marvelous smile and a reassuring attitude. “Just a bad case of malaria.”

The nurse continued her rounds as one of the Red Cross volunteers—women who helped the nurses meet the soldier’s basic needs for comfort by washing faces, giving drinks of water, lending a listening ear, and assisting soldiers when writing letters home. She picked up a chart hanging on the foot of the cot next to Phil’s.

The chart listed the patient’s name and where and how the patient was wounded. Phil noticed her eyes widen.

“How on earth did you ever get shot with two arrows?” she blurted to the soldier.

Phil looked at the man, obviously from some Indian tribe because of his complexion and straight black hair.

“That’s my name, not my injury!” he replied with consternation.

Note: At the start of World War II, there were fewer than a thousand nurses in the Army Nurse Corps. Initially, the ANC took only unmarried women between the ages of twenty-two and thirty who had their RN training from civilian schools. By the end of the war, the ANC had 54,000 nurses—all women.

Note: Prior to the war, Mussolini had dug canals and installed pumps to drain the marshes on the Anzio plain to create farms. Before the invasion, the Germans reversed the pumps, flooding the canals and low-lying fields. This became a perfect breeding ground for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Historians debate whether this was a case of biological warfare or not.

Note: Six Allied divisions—approaching 100,000 troops—now occupied eighty square miles, hey plot slightly larger the district of Columbia. Since the epic struggles of February, a sullen stalemate had obtained. Newcomers found got life in the Beachhead Army was not only subterranean but nocturnal, with a battle rhythm known as “Dracula Days.” Soldiers near the “dead country”—the no man’s land between the opposing armies—often slapped in their holes until four P.M,, patrolled until three A.M., ate a hot meal before sunrise, and slipped under ground until the next afternoon. “Rumors slide from hole to hole,” wrote Audie Murphy, now a platoon sergeant in the 3rdDivision. “We believe nothing, doubt nothing.” At night the beachhead turned restless, with raids, patrols, harassing fire, and chandelier flares that stretched men’s shadows grotesque like. … Bill Mauldin noticed that during barrages, military policemen remained in their crossroads trenches and controlled traffic by “holding up a wooden hand to point directions.”[1]

[1] Atkinson, The Day of Battle, 486.

Note: The demand for sandbags and barbed wire along the thirty-two-mile perimeter had reached Flanders proportions. The “Anzio Ritz” was an underground cinema, given to grainy showings of Cary Grant in Mr. Lucky. On fine mornings, a British soldier wrote, men beyond sniper range sunned themselves on the lip of their holes “but with one ear cocked, like rabbits ready to pop back in again.” Soldiers kept their helmets on so long they wore bald spots in their scalps. “men dream of steaks, milk, toilet seats, running water, and the exquisite problem of what color clothes to wear,” a 179th Infantry account noted. Everyone grumbled at the static “Stizkrieg” war. One physician compiled a beachhead glossary that included “anziopectoris”—a general indisposition—and “anziating,” a distant look in the eyes. Beachhead denizens called themselves “Anzonians,” and not without pride.[1]

[1] Atkinson, The Day of Battle, 486.

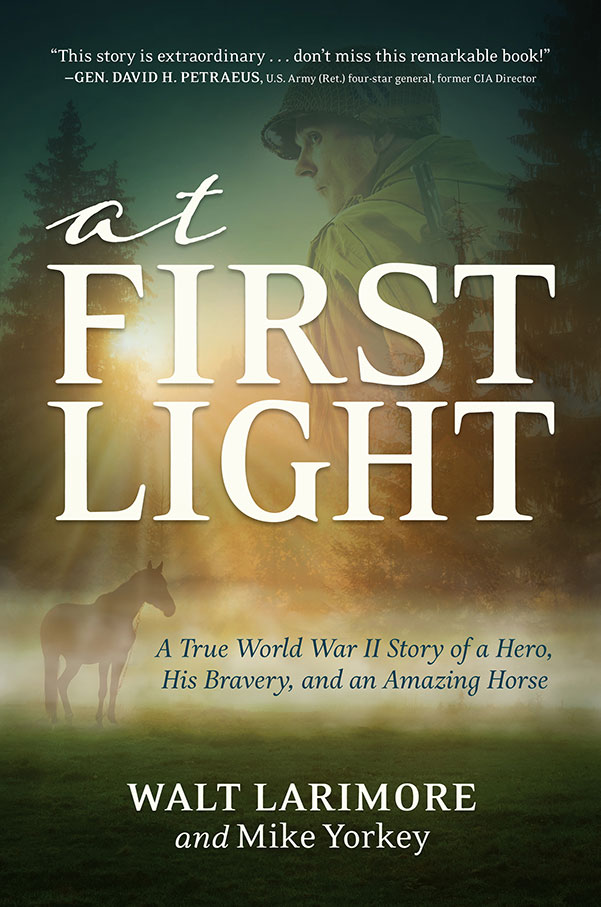

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.