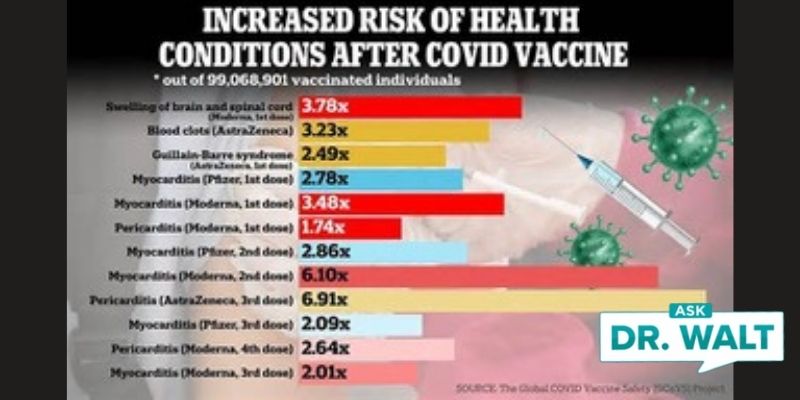

Largest COVID vaccine study yet finds up to 3 times greater risk? True or false?

March 13, 2024

March 14, 1944 – Skirmishes increase on the Anzio front line

March 14, 2024While writing the early drafts of my book, At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse, I left much of my research on the cutting floor. Here are some neat stories about Army nurses in WWII you might enjoy. The one about LT. Frances Slander will bring a tear to your eyes.

Army Nurses

(In the) evacuation hospital … the first sight many of them saw was a nurse from the Army Nurse Corps (ANC). She was harassed, wearing fatigues, exhausted, and busy. But she was an American girl, she had a marvelous smile, a reassuring attitude, and gentle hands. To the wounded soldier, she looked heaven sent.[1]

These pioneers had to overcome many obstacles. The first was the act of volunteering. There was a nationwide slander campaign about women in uniform, as vicious as it was false. The jokes were gross. They were told by rear-echelon soldiers and civilians. No one who have ever seen an Army nurse in action in the field hospital, nor any wounded soldier, ever told such jokes. But because they were so widely told by people who didn’t know what they were talking about, recruitment slow down to a trickle. A questionnaire showed that of those nurses who did volunteer, 41 percent had to overcome opposition of close relatives. Only half said their closest male friends were supportive, whereas 80 percent of their closest female friends had supported their decisions.[2]

Under the circumstances, recruitment was insufficient. To speed it up, the Army made the ANC more attractive. From June 1944 onward, nurses were given officers’ commissions, full retirement privileges, dependents’ allowances, and equal pay. And the government provided free education to nursing students. The continuing shortage of nurses meant of those who served at field or evacuation hospitals we’re badly overworked.[3]

One untapped source was African-American nurses. When the war ended there were only 479 black nurses in a corps of 60,000. This is because the Army assigned the quota, not because the black nurses didn’t want to serve. But in the America of that day, it was unthinkable that black nurses could care for white American soldiers. In June 1944 one unit of sixty-three African-American nurses went to a hospital in England, to care for German POWs.[4]

(On particularly bad days of battle, when there were many casualties), the ambulances coming from the battalion stations had to line up, three abreast, in lines reaching up to 200 yards. The … doctors worked as rapidly as possible but we’re only just able to keep up with the litter bearers caring patients in from the ambulance and out the back of the receiving tent. Not only were litters coming and going; there was space for 100 litters in the tent and they were nearly always filled. There were litters bearing wounded men in open spaces on the ground outside the tent. Along the sides of the tent sat the walking wounded, clutching their souvenirs. A tag showed whether and how much morphing the casualty had received from the medic. The doctors went from patient to patient, asking questions, scanning each record, listing the dressings to check each wound.[5]

The nurses changed dressings, administered medications, checked each record, monitored the vital signs, and while they were doing those jobs they rearranged the blankets and gave the soldier a smile. They were too busy to do much more. … Red Cross volunteers helped meet the need for comfort. … Red Cross hospital worker Beatrice Cockram described her activities and emotions: “To walk down a ward virtually made my heart bleed to see how much was to be done just washing faces and giving drinks water. The nurses are too busy with the vital blood plasma, penicillin and sulfa treatments.”[6]

Funny stories helped them keep going. One concerned a Red Cross worker, Miss Eisenstadt, who picked up a chart expecting to see where and how the patient was wounded. What she saw astonished her.

“How on earth did you ever get shot with two arrows?” she blurted out.

The full-blooded American Indian on the cot replied with righteous indignation, “That’s my name, not my injury!”[7]

Lt. Aileen Hogan was forty-two years old when she volunteered for the ANC a few days after Pearl Harbor. … She described her duties on the penicillin team. “At seven [1900 hours] all the penicillin needed for the first-round is mixed and two technicians and one nurse make the rounds of the hospital giving penicillin to the patients. One loads the syringes and changes needles, the other to give the hypos. At the rate of 60 to a tent, one gets groggy. It is an art to find your way around at night, not a glimmer of light anywhere, no flashlights of course, the tents just a vague silhouette against the darkness, ropes and tent pins a constant menace, syringes and precious medications balanced precariously on one arm.”[8]

Like many of the nurses, (Ruth) Hess found herself weak with admiration for the wounded men. Another hero, Lt. Frances Slanger of the 45th Field Hospital expressed the feeling in an October letter addressed to Stars and Stripes but written to the troops: “You G.I.’s say we rough it. We weigh ankle deep in mud. You have to lie in it. We have a stove and coal. … In comparison to the way you men are taking it, we can’t complain, nor do we feel that bouquets are due us. … It is to you we doff our helmets.

“We have learned about our American soldier and the stuff is made of. The wounded don’t cry. Their buddies come first. The patience and determination the show, the courage and fortitude they have is sometimes awesome to behold. It is a privilege to receive you and a great distinction to see you open your eyes and with that swell American grin, say, “Hi-ya, babe.’ ”

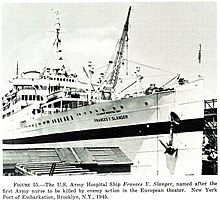

Slanger was killed the following day by an artillery shell. She was one of seventeen Army nurses killed in combat.[9]

~~~~~

More about Slanger from Wikipedia:

On October 21, 1944, Slanger submitted a letter to Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper:

It is 0200, and I have been lying awake for an hour listening to the steady breathing of the other three nurses in the tent, thinking about some of the things we had discussed during the day.

The fire was burning low, and just a few live coals are on the bottom. With the slow feeding of wood and finally coal, a roaring fire is started. I couldn’t help thinking how similar to a human being a fire is. If it is not allowed to run down too low, and if there is a spark of life left in it, it can be nursed back. So can a human being. It is slow. It is gradual. It is done all the time in these field hospitals and other hospitals at the ETO.

We had several articles in different magazines and papers sent in by grateful GIs praising the work of the nurses around the combat zones. Praising us – for what?

We wade ankle-deep in mud – you have to lie in it. We are restricted to our immediate area, a cow pasture or a hay field, but then who is not restricted?

We have a stove and coal. We even have a laundry line in the tent.

The wind is howling, the tent waving precariously, the rain beating down, the guns firing, and me with ta flashlight writing. It all adds up to a feeling of unrealness. Sure we rough it, but in comparison to the way you men are taking it, we can’t complain nor do we feel that bouquets are due us. But you – the men behind the guns, the men driving our tanks, flying our planes, sailing our ships, building bridges – it is to you we doff our helmets. To every GI wearing the American uniform, for you we have the greatest admiration and respect.

Yes, this time we are handing out the bouquets – but after taking care of some of your buddies, comforting them when they are brought in, bloody, dirty with the earth, mud and grime, and most of them so tired. Somebody’s brothers, somebody’s fathers, somebody’s sons, seeing them gradually brought back to life, to consciousness, and their lips separate into a grin when they first welcome you. Usually they say, “hiya babe, Holy Mackerel, an American woman” – or more indiscreetly “How about a kiss?”

These soldiers stay with us but a short time, from ten days to possibly two weeks. We have learned a great deal about our American boy and the stuff he is made of. The wounded do not cry. Their buddies come first. The patience and determination they show, the courage and fortitude they have is sometimes awesome to behold. It is we who are proud of you, a great distinction to see you open your eyes and with that swell American grin, say “Hiya, Babe.”[10]

When the letter arrived at the magazine, the staff were so impressed that they chose to publish it as an editorial. It quickly found popularity, proving so inspirational that many readers, military and civilian alike, wrote to her to thank her for her sentiments.[10] But Slanger never saw the acclaim her letter received; hours after writing it, she was killed by a barrage of artillery in the field, becoming the only American nurse to fall to enemy action in the European theater of the war.[11] It was reported that even as she was dying, she expressed concern for those others who had been injured in the fighting.[10] Slanger died in Elsenborn, Belgium.[12] Initially buried in France, in a military cemetery, her remains were repatriated in 1947, to be reinterred at the Independent Pride of Boston Cemetery in Roxbury.[10] Boston’s mayor was among the thousands who paid their respects at the ceremony.[12]

~~~~~

[1] Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 321-322.

[2] Campbell, “Servicewomen of World War II,” 254. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 322.

[3] Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 322.

[4] Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 322.

[5] 118. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 323.

[6] Litoff and Smith, This is War, 9. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 323-324.

[7] Allen, Medicine Under Canvas, 140. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 325.

[8] Litoff and Smith, We’re in This War, Too, 164. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 324.

[9] Litoff and Smith, We’re in This War, Too, 169. Quoted in: Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, 326.

[10] “Profile: Frances Slanger”. Dec 4, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

[11] “Second Lieutenant Frances Slanger, Army Nurse Corps – The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army”. Retrieved February 25,2020.

[12] “Army nurse Frances Y. Slanger killed by German artillery | Jewish Women’s Archive”. jwa.org. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.