Should one pray for healing only versus seeking medical care only?

March 10, 2024

March 12, 1944 – Dad’s admiration for the amazing Army nurses

March 12, 2024After dinner that evening at the field hospital on the Anzio beachhead, Second Lieutenant Phil Larimore, who had been hospitalized with malaria, felt well enough to walk to the stove at the end of the officer’s ward tent to have a smoke. He pushed the pole holding the IV flowing into his arm.

“Can I sit with you?” one of the nurses asked.

“I’d be crazy to refuse an offer like that.” Phil clicked his Zippo[1] to light her cigarette. “You look tired. Long day, eh?”

The nurse blew out her first puff. “Every day’s long here on the ‘Bitchhead.’ But we sure had a strange encounter in the OR this morning. Received two frontline men who’d been shot last night while patrolling behind enemy lines. When the surgeons went in to clean out the wounds, which were not fatal, they found wooden bullets.”

Phil thought he hadn’t heard right. “Wooden bullets?”

“Yes, sir,” she replied. “It’s happened a few times before. The bullet is made in the pattern of a regulation .30-caliber cartridge with a brass casing and hardwood-like mahogany pressed inside. The Krauts use them at night, especially when they send a patrol behind our lines. That’s when they open up on our boys with these wooden things. Their range is short. That way, their bullets don’t go past our men and back into their lines.”

Phil laughed. “I hadn’t heard about that.”

The nurse inhaled another draw. “Who’s waiting for you back home, soldier?” she asked.

“A special gal.”

Phil reached into his vest pocket and took out a picture of Marilyn. “She says she wants to marry a doctor. Maybe I’ll go into medicine when I get back to the States.” He took a puff. “So, tell me: What’s the most stressful part of your work here on the beachhead?”

She thought a moment. “There are two things. The first is the fact that we nurses are often the last person a soldier sees or touches or talks to before he dies. It’s hard to see so many die so horribly. You don’t forget something like that. Not ever.” Her eyes misted as she solemnly flicked ash into an ashtray.

“The OR is the second big stress,” she continued. “If we’re in the wards or our sleeping quarters and the shelling begins, we can duck into the bomb shelters dug into the berms surrounding each tent. But if we’re in the OR in the middle of surgery, we can’t stop unless absolutely necessary. A corpsman will go by each OR table and place a helmet on the head of each doctor and nurse and one over the patient’s face. Even then, we might have to hit the ground when shrapnel comes through the tents, but we get up immediately and continue once the danger has passed.”

She took a long draw on her cigarette and flicked off more ash. “For us nurses, just like for you boys, everything is based on trust. We’re in a war zone, and we nurses trust each other to a tee. But we never talk about what we see or what we do each day. I don’t think we can. We all know that we could get killed, but none of us dwell on the fact. We just do what we need to do. If we get hit, that’s just the way it is.”

Phil felt his head nod in agreement as he watched her stub out her cigarette and stand up.

“Back to work for me, Lieutenant. Thanks for letting me unload. I think that most any sorrow can be borne if we’re able to share our story with someone.”

“Think nothing of it.”

She smiled. “It’s hard, but I think once we share them, it softens the pain.”

Phil made eye contact with this angel in white, who leaned over and kissed him on the forehead. “Thanks for listening,” she whispered. “Break a leg.” [2]

[1] The most common Zippo lighter used by the GIs was the Black Crackle Zippo, which was covered with a special black crackle paint that would not reflect light, thereby avoiding the attention of enemy snipers.

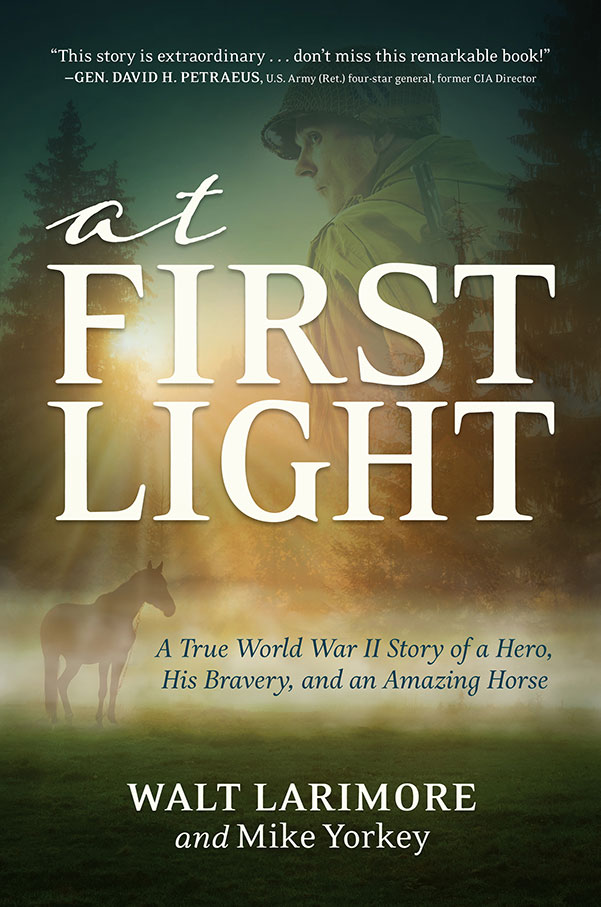

[2] From: At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse, Chapter 16, “Opening Salvo.”

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.