February 23, 1944 – A teenage WWII hero’s faces his first death on the front line at Anzio

February 23, 2024

My “Ask Dr. Walt” column in Today’s Christian Living on Acupuncture, Cooking Oils, and Vitamin Water

February 26, 2024February 24, 1944 – A teenage WWII hero’s men comment of their first days on the front-line in war

Young men made many many discoveries in the first few days of combat, about war, about themselves, and about others on the front line in World War II — especially those in Phil Larimore’s A&P platoon who had to lay down booby traps and mines in “no man’s land” at night, often just a a few dozen yards from Germans and their machine gun nests.

Opening Salvo

“As we entered combat, I had a strange feeling. All my life, I felt secure, knowing the United States would protect me, but now it was reversed. The country was now depending on me to protect them. It was an awesome feeling, but I was not sure I could bear so much weight.”

Although Phil was younger than any of his men, he was pleased with how they welcomed him. Like most rookie soldiers, he wasn’t sure how he’d respond to active combat. When he entered the Anzio war zone, though, he was gratified to discover that he wasn’t a coward and didn’t run away or collapse into a pathetic mass of quivering Jell-O.

He remembered his training—that fear was inevitable but could be managed. At the same time, Phil understood there was no way training could have prepared him for the reality of combat. He, along with his men, had to learn how to survive a live battlefield.

One example was the “three-second rule” that one of Phil’s sergeants taught him. If an enemy soldier drew a bead on you during a firefight, he was told back in Alliance, Nebraska, it took him three-fourths of a second to locate you. Then it took him another second and a half to raise his weapon and another half a second to put you in his sights. Three seconds was all you had, so that’s why, when you came under fire, you had to hit the ground and roll and not get up in the same spot because there might be a bullet waiting for you.

~~~~~~~

The men on the front lines quickly learned such basics as keep down or die—to dig deep and stay quiet—to distinguish incoming from outgoing artillery—to judge when and where a shell or a mortar barrage was going to hit—to recognize that fear is inevitable but can be managed—and many more things they had been told in training but that can only be truly learned by doing. Putting it another way, after a week in combat, infantrymen agreed that there was no way training could have prepared them for the reality of combat.

Capt. John Colby caught one of the essences of combat, the sense of total immediacy: “At this point we had been in combat six days. It seemed like a year. In combat, one lives in the now and does not think much about yesterday or tomorrow.”

Another thing Colby learned in his first week in combat was: “Artillery does not fire forever. It just seems like that when you get caught in it. The guns overheat or the ammunition runs low, and it stops. It stops for a while, anyway.”

He was amazed to discover how small he could make his body. If you get caught in the open in a shelling, he advised, “the best thing to do is to drop to the ground and crawl into your steel helmet. One’s body tends to shrink a great deal when shells come in. I am sure I have gotten as much as eighty percent of my body under my helmet when caught under shellfire.”

The men were also learning about others.

A common experience: the guy who talked the toughest, bragged the most, excelled in maneuvers, everyone’s pick to be the top soldier in the company, was the first to break, while the soft-talking kid who was hardly noticed in camp was the standout in combat.

These are the clichés of war novels precisely because they are true.

They also learned that while combat brought out the best in some men, it unleashed the worst in others—and a further lesson, that the distinction between the best and worst wasn’t clear.

Pvt. Arthur “Dutch” Scchultz … was part of an attack on the town. “I ran by a wounded German soldier lying alongside of a hedgerow. He was obviously in a great deal of pain and crying for help. I stopped running and looked around. A close friend of mine put the muzzle of his rifle between the German’s still crying eyes and pulled the trigger. There was no change in my friend’s facial expression. I don’t believe he even blinked an eye.”

Schultz was simultaneously appalled and awed by what he had seen. “There was a part of me that wanted to be just as ruthless as my friend,” he commented. Later, he came to realize that “there but for the grace of God go I.”

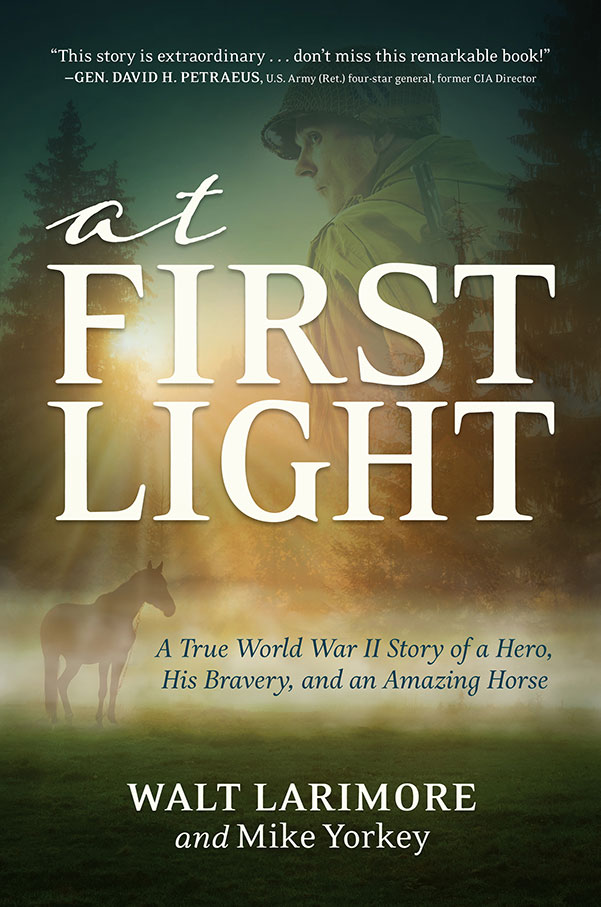

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.