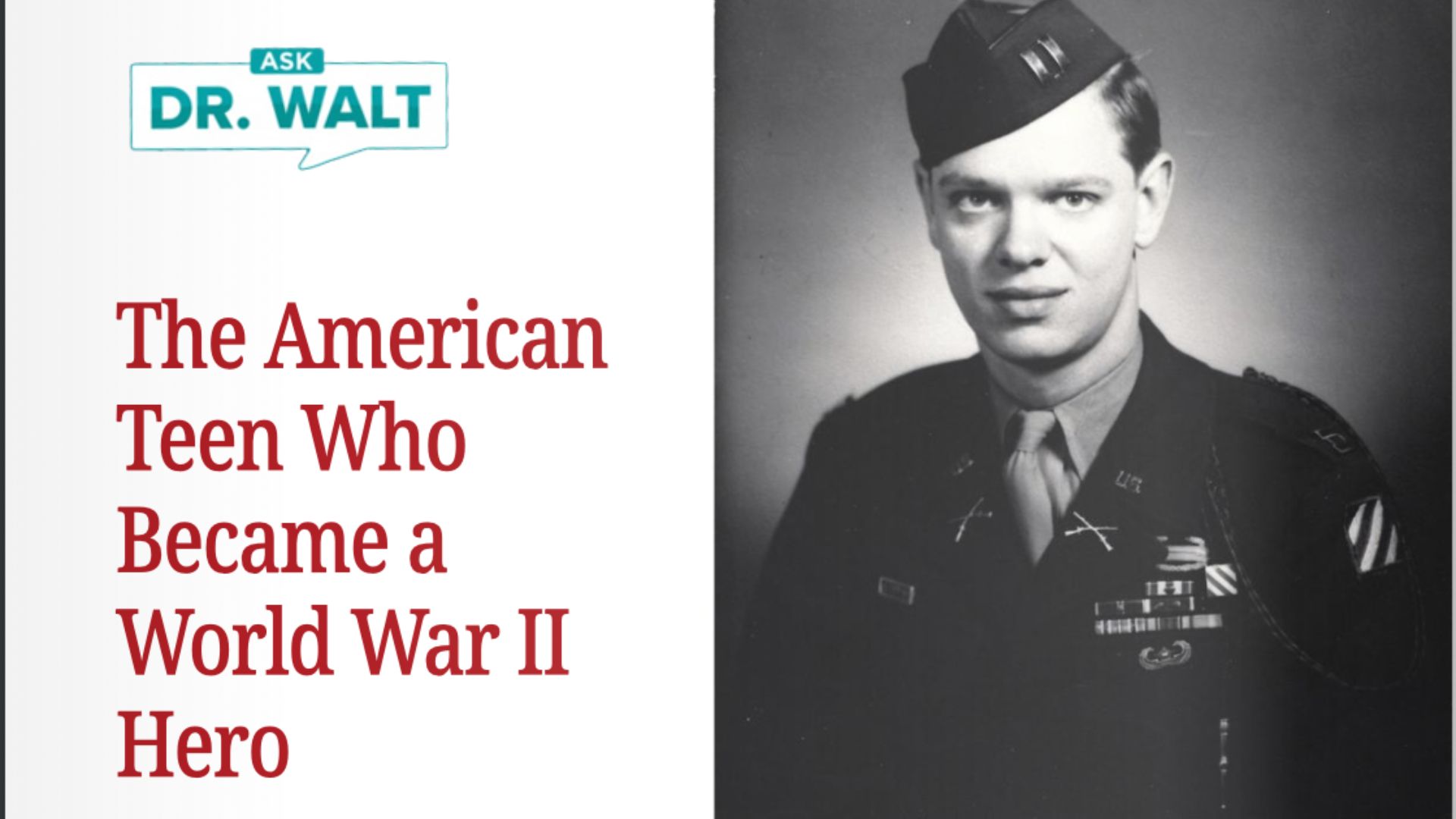

The American Teen Who Became a World War II Hero (magazine article from London)

February 28, 2024

List of my February 2024 Blogs on “Where was Dad 80 years ago today?”

March 1, 2024On February 29, 1944, as the first streaks of light glinted on the snow-covered peaks of the Lepini mountains ringing the beachhead, regimental command had Phil and most of his platoon head toward the division’s left sector. This was where the 3rd Battalion expected to receive a major attack by at least one enemy battalion. A promising nice day quickly turned into a freezing, rainy morning,

Phil and his men got busy placing wire and mines in front of the American troops and mining and cratering the roads leading into enemy territory. They also became a vital part of the supply chain.

After less than two weeks on the job, Phil had instilled into his men the determination to get the ammo, grenades, and mortar shells[1] to the combat men without delay and fight with the frontline men when necessary.

In other words, whenever one of his squads delivered ammunition into a dangerous area and a small arms engagement erupted, they joined in the battle.

When the anticipated assault came, Company I was hit by at least two enemy infantry companies in the first wave of the attack. The Germans poured intense machine gun and rifle fire on the American soldiers. Phil’s men kept the ammunition supply line fed up to the Main Line of Resistance (MLR), which was extremely dangerous because of the machine gun, rifle, and small arms fire, along with an increasing barrage with mortar and artillery shells, some landing as close as twenty yards.

Prodded by Hilter, Kesselring, and Mackensen … The usual singing, shouting, gray-green swarms advanced across the polders only to be flattened, yet wave upon wave of enemy infantry continued to storm positions supported by dozens of tanks. The Germans attacked in relentless waves. Shivering Yanks stood in freezing foxholes, forcing themselves to hold their guns steady. Down to the draws came figures in long green overcoats and shining mess gear. American machine guns played back and forth, but the Germans kept coming over the bodies of the dead.

The frontline soldiers continued to hold off all enemy advances with continuous small arms and automatic weapons fire. They provided enfilade fire[2] against the enemy units that had penetrated the battalion lines as heavy fighting continued in the 3rd’s sector throughout the day.

Although heavy clouds and squalls nullified the Allied air support in the morning, the skies cleared by the afternoon. Beginning at 1500, Allied bombers appeared to the cheers of the men up and down the front as they watched their planes pummel the enemy attackers. They witnessed quite a demonstration of American air power as 247 fighter bombers, along with twenty-four light bombers, bombed and strafed enemy armor and infantry close to the lines.

Along with the air support, the U.S. artillery and armor pelted the Germans with over 66,000 Allied artillery shells in a single day. In the attacks on the west flank of the 3rd Division front, which had begun at daylight, the Germans had gained some ground but were unable to exploit their penetration.

A single 105mm howitzer shooting every thrity seconds could, in one hour, seed 43,000 square yards with two tons of lethal steel fragments. Allied artillery inflicted three-quarters of all German battle casualties at Anzio. … Some LCIs sailing from Naples now carried a hundred tons of ammunition, triple the prudent load, and Navy brokers had begun identifying civilian schooners for use as cargo vessels.

Finally, the massed American fire forced the enemy to withdraw. German casualties topped 3,500 for no gain.

When Alexander asked General O’Daniel how much ground his 3rd Division has lost to the counterattackers, Iron Mike replied, “Not a goddamned inch, sir.”

General Truscott had pinned a Bill Mauldin cartoon over his desk, with one shabby GI telling another, “Th’ hell this ain’t the most important hole in th’ world. I’m in it.”

Still, February was sobering for the Allies. For the Americans it would be the bloodiest month in the Mediterranean to date, with nineteen hundred dead.

For a second time in one month, the 30th Infantry had successfully completed a counterattack against a major German salient into the Beachhead lines. Once again the 30th Infantry had clearly upheld its reputation of always doing the job. … The 30th Infantry Company Team proved itself a team to beat twice within two week in the month of February 1944, a month which figures brightly in Regimental annals.

Exhausted, the Germans reverted to the defensive on March third. The commanding general of the British 1st Division, also locked in the Anzio beachhead, sent a thankful message to the 3rd Division: “Congratulations on your work out there.”

Following the German counterattack, “the beachhead remained a salient of fifteen miles wide and ten miles deep,” raked constantly with artillery fire from a determined enemy, who “held the high ground back from the beach.”

Field Marshall Kesselring’s forces encircled and hemmed in the beachhead with some five hundred guns: including two 280 mm railroad guns (“Anzio Annies”—”big eleven-inch artillery … it was a terrific sounding gun. It sounded like a railroad box car coming end over end”), two 240 mm railroad guns, a number of 210 batteries, many 170 mm rifles, 150 mm and 105 mm howitzers, and scores of 88 mm anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns. The effectiveness of the German artillery was reflected in the number of 3rd Division casualties — 70% caused by shell fragments.

The night of February 29, after the German shelling finally stopped, Phil had a bit of time to clean his weapons while reflecting on surviving his first couple of weeks on the battle lines.

He felt he had proven himself and now had a good idea of what to expect and what was expected of him. He and his men were no longer strangers thrown together randomly by war. Now they were veterans of combat together.

More importantly, Phil had lived to fight another day, and the beachhead was quiet — for a moment.

[1] The M2 mortar was a 60-mm smooth-bore, muzzle-loading, high-angle-of-fire weapon used by the GIs in World War II for company-level fire support. The firing pin was fixed in the base cap of the tube, and the bomb was fired automatically when it dropped down the barrel. Depending upon the shell, the mortar had a range of 200 to 2,000 yards.

[2] Enfilade fire is when weapons are trained across the longest part of an enemy formation.

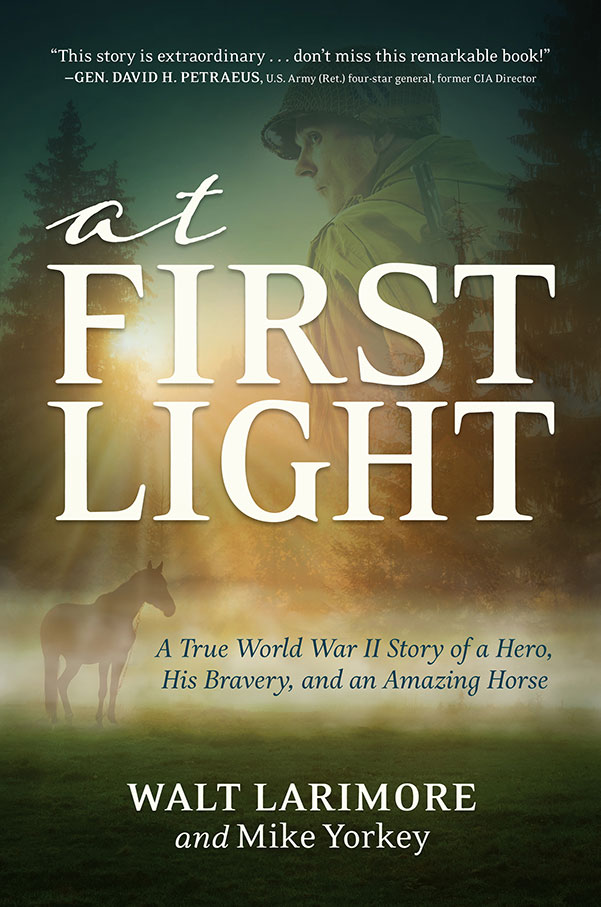

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.