My “Ask Dr. Walt” column in Today’s Christian Living on over-the-counter hearing aids and health risks from Wi-Fi routers

February 9, 2024

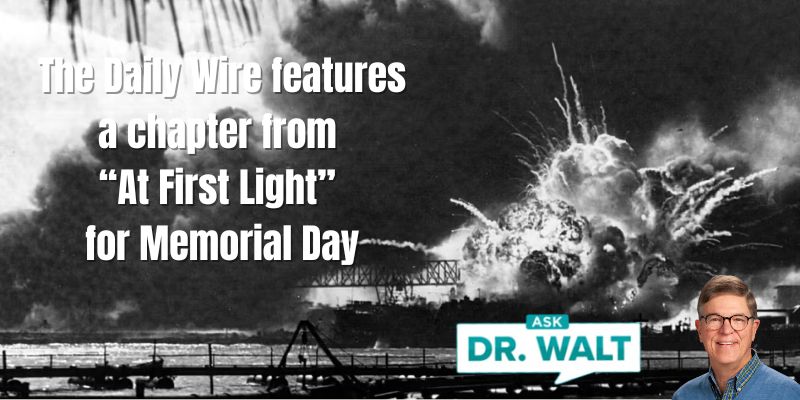

February 11, 1944 – A teenage WWII hero writes home from French Morocco

February 11, 2024On the Liberty Ship, 18-year-old, Phil Larimore, the youngest commissioned Army officer in World War II, stood on the deck and watched his homeland disappear over the horizon as he and 5,000 men were on a nine-day trip through the treacherous North Atlantic and the potential of being sunk by any number of marauding packs of German U-boats.

It wasn’t long before many of the men got seasick. Even though the soldiers weren’t able to smoke below deck or get any exercise, they took the sketchy meals, lack of privacy, and relaxed hygiene standards in stride. They managed to laugh and poke fun at it all, and at themselves, cursing Hitler roundly at all times.

Phil found himself reminiscing the last days before sailing:

On January 30, 1944, he boarded a train at Camp Patrick Henry that would transport the men to Norfolk, Virginia, on the Chesapeake Bay. His eyes focused on three war posters plastered on the front wall of their carriage.

The first said, “Americans Will Always Fight for Liberty.” He had seen this depiction of three modern American riflemen marching in front of their military ancestors—three infantrymen from the Continental Army of 1778—many times before.

The second poster made him smile. The graphic pictured an oversized caricature of Hitler falling backward, having been tripped by an Army truck. At the top, a headline said, “Knock the ‘Heil’ Out of Hitler,” and across the bottom, it read, “Let’s Keep ’Em Pulling for Victory.”

Liberty and victory. A nice series of encouragements, Phil thought, for guys like me who are getting ready to go overseas and fight.

Then his eyes fixed on the last poster, a colorful illustration of a young woman who looked a bit like his Marilyn. She wore a red-and-white polka-dot bandana around her head and was flexing her right bicep, which was visible since she had rolled up the sleeve of her blue blouse.

Across the top, a headline announced, “We Can Do It!” Phil knew he would. Well, at least he hoped he would, as the train entered the shipyard. He knew that it was up to him to fight to get back to her, and he would.

As the railway cars drew closer to the docks, Phil spotted ships of all sizes as far as the eye could see. As the train pulled into a platform under protective roofing, literally stopping next to their Liberty ship, Phil put on his overloaded backpack and grabbed his duffel-like barracks bag. As he stepped off the railroad car, he was checked off a list and marched toward the waiting ship.

Young female Red Cross workers handed out cups of coffee from fifty-gallon stainless steel containers to each of the boys who wanted them. Then each soldier was checked off another list as he boarded the gangplank onto the ship under the watchful eyes of Army military police and Navy shore patrol. Each man struggled to carry his load up a steep and narrow ramp.

Phil was directed below decks to officer’s quarters, where eight officers were assigned to cabins with two-tier bunks with springs and mattresses. In comparison, the enlisted soldiers were shoehorned into tighter quarters with four to five tiers of bunk beds that nearly touched the ceiling. The space between bunks was so narrow that one had to walk sideways to get through, and there was no place to store a barracks bag except on the bunk.

There was considerably more room inside the officer’s quarters. While Phil knew he wasn’t staying in first-class accommodations, he realized that he had it better than most. Maybe the long trip wouldn’t be so bad after all.

On Wednesday, February 9, 1944, the Liberty ship docked at Casablanca in the North African country of French Morocco.

Phil and his men knew this wasn’t their final destination. By now, even the naivest soldier had figured out that they were going to Italy, where the Allies were being clobbered at Cassino and the 3RD Infantry Division had just landed at Anzio during their fourth amphibious landing on a foreign shore. The 3RD Battalion of the 30th Infantry Regiment had also had two additional amphibious landings in Sicily.

He wrote home on Thursday, February 10, 1944:

Philip B. Larimore 2nd Lt., 0-511609, A.P.O 15148, North Africa, Base 0419

Dearest Mother;

At last I stop long enough that I can write a letter. I don’t know for sure what I will say cause there isn’t too much they will let us say.

We had a very nice trip across, only had one or two days that were anywhere near bad and that wasn’t too much, but all in all I enjoyed it and I didn’t get any where net sick.

We had very good meals on the ship, the Navy sure does eat swell. I think in the next war I’ll get into the Navy. Do you think my Army family would let me?

When we got here we were tired but I think a happy bunch.

Will write more later.

With love, Phil

Now he and the men could only wait to see what would happen next.

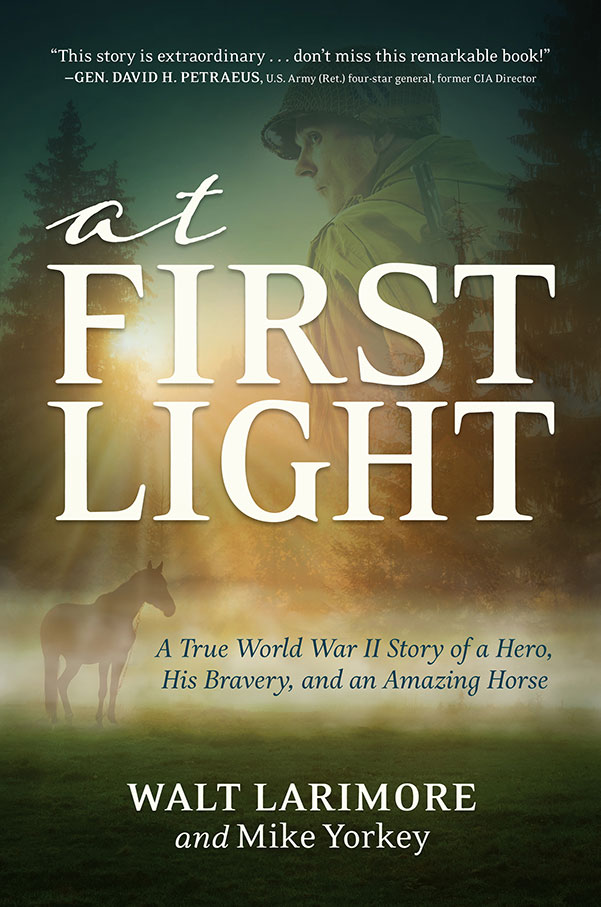

In case you haven’t read or listened to Dad’s book, you can learn more or order it here.

© Copyright WLL, INC. 2024.